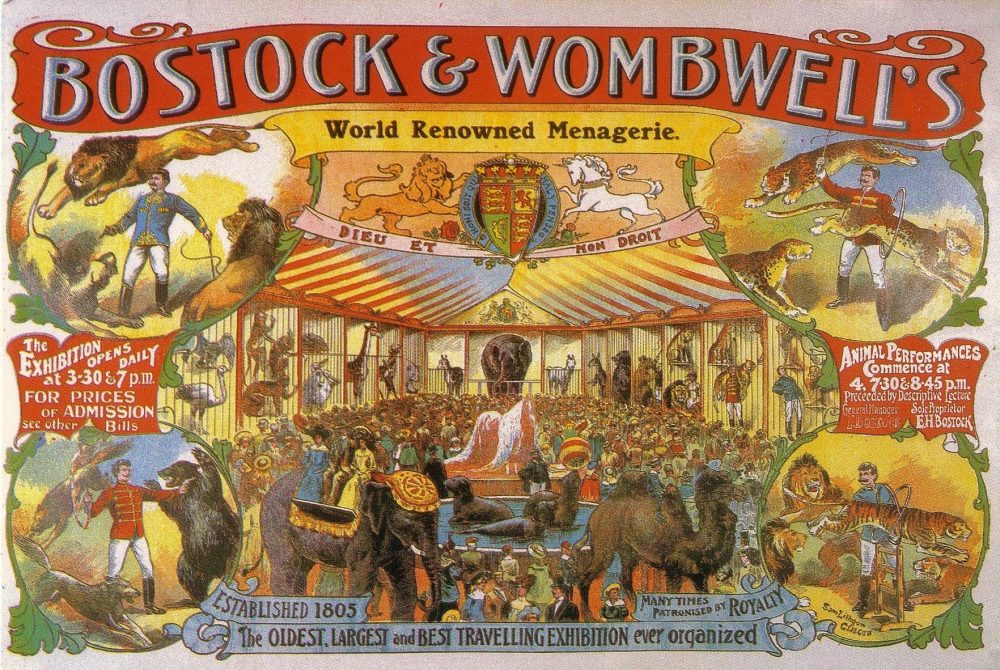

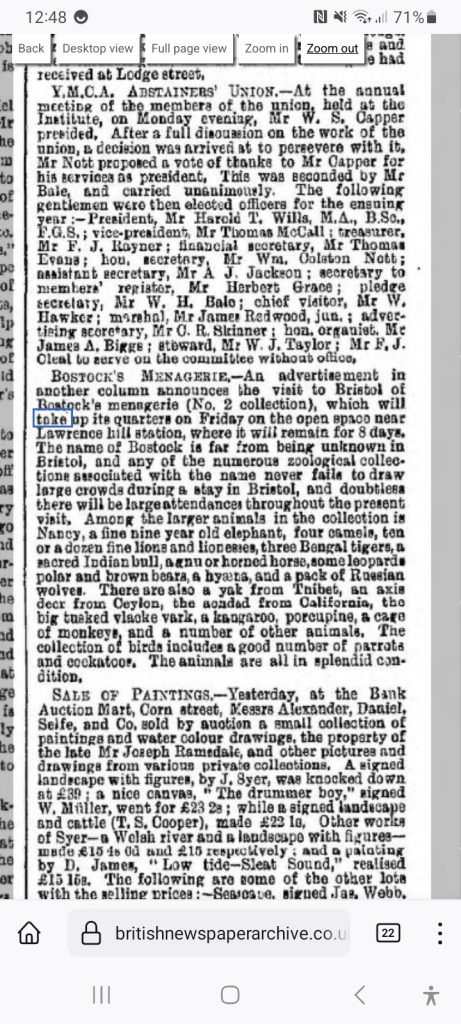

The travelling menagerie, which refers to the practice of showcasing exotic animals in traveling shows and circuses, can be understood in the context of imperialism and its association with Great Britain during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The menageries were closely tied to the imperial ambitions of Britain and other European powers during this period. Here are some key points to consider:

- Imperialism and Exploration: During the height of imperialism, European powers sought to expand their influence and control over vast territories across the globe. Explorers and colonialists ventured into newly acquired territories, discovering and capturing exotic animals they encountered. These animals were brought back to Europe and showcased in travelling menageries as symbols of the empire’s conquests and the exotic lands under their dominion.

- Colonial Trade and Exploitation: The establishment of British colonies around the world created networks of trade and exploitation. The capture and transportation of exotic animals were part of this colonial enterprise. These animals were often taken from their natural habitats, sometimes under cruel conditions, and transported long distances to be displayed in Europe. This practice exemplified the exploitation of natural resources and living creatures that was prevalent during the era of imperialism.

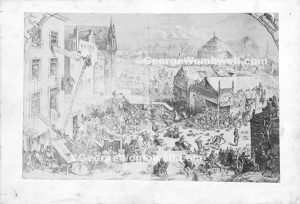

- Representation of Dominance: The exhibition of exotic animals in travelling menageries served as a display of the British Empire’s dominance and power over foreign lands and peoples. The menageries presented a visual spectacle for the British public, reinforcing the idea of Britain’s superiority over the territories it had colonized.

- Cultural Othering and Racism: The showcasing of exotic animals also contributed to the “othering” of non-European cultures. It perpetuated a sense of Western superiority over the “exotic” and “primitive” cultures from which the animals came. This same mindset was applied to indigenous peoples in the colonies, as they were often portrayed as inferior and in need of European guidance and control.

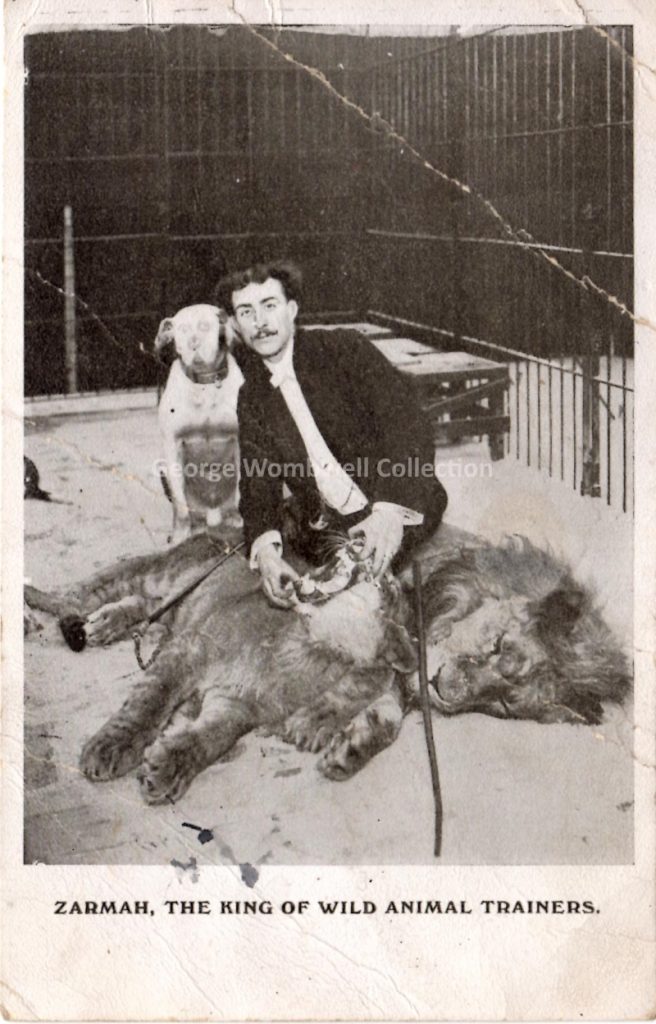

- Public Entertainment and Education: Travelling menageries were not only about imperialism and power; they also served as popular forms of entertainment for the British public. People flocked to see these exotic creatures, as many had never encountered such animals before. These exhibitions fed into a growing fascination with the exotic and unknown, contributing to the development of Victorian-era curiosity and interest in the natural world.

- Ethical Concerns and Conservation: As attitudes toward animal welfare and conservation evolved over time, the ethics of keeping animals in captivity and displaying them for human entertainment were increasingly questioned. Modern sensibilities recognize the harm caused to both animals and their ecosystems by the practice of capturing and displaying them in menageries.

In conclusion, the travelling menagerie can be seen as a manifestation of British imperialism during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a practice closely tied to the exploration, exploitation, and display of the empire’s conquests, showcasing the exotic and wild aspects of lands under British control. Today, the historical context of the travelling menagerie serves as a reminder of the complexities and consequences of imperialist endeavors and the changing attitudes toward animal welfare and conservation.