Tacita Dean, a renowned contemporary artist, has left an indelible mark on the art world with her distinctive approach to storytelling and her exploration of themes such as time, memory, and the inherent qualities of film. Through a variety of mediums, including film, drawing, and photography, Dean’s artworks invite viewers to engage with the poetic nuances of existence. This essay delves into five notable examples of her work that showcase her unique artistic vision.

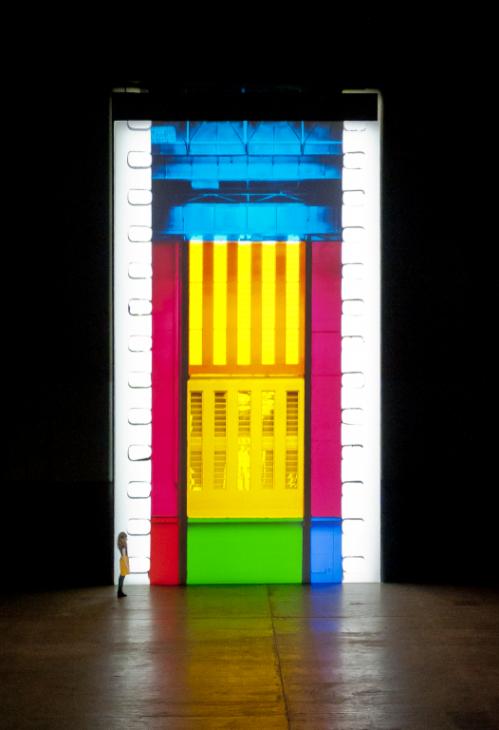

Tacita Dean, FILM, 2011, Film, 35mm, projection, black and white and colour, Duration: 10min, 42sec

1. “FILM” (2011): One of Tacita Dean’s most acclaimed works, “FILM” is a 35mm film installation that captures the allure of the cinematic medium. The piece features a loop of unedited footage, embracing the materiality of film itself. By drawing attention to the physicality of the medium, Dean encourages viewers to reflect on the endangered status of traditional film in the digital age.

2. “The Green Ray” (2001): In this film installation, Dean explores the elusive natural phenomenon known as the “green flash” or “green ray” that occurs during sunset. Through meticulous observation and poetic narration, she transforms a fleeting moment into a contemplative experience. The work reflects Dean’s fascination with the intersection of nature and perception.

3. “Event for a Stage” (2015): This multi-channel film installation captures a live performance by actor Stephen Dillane. Dean’s emphasis on the theatricality of the event and the merging of reality and fiction highlight her interest in narrative structures. “Event for a Stage” offers a unique exploration of the dynamics between performer and audience.

Ariel view of the wreckage and surrounding landscape

4. “Teignmouth Electron” (1999): In this film installation, Dean revisits the story of Donald Crowhurst, a sailor who embarked on a disastrous solo voyage around the world. By combining found footage with her own, Dean constructs a layered narrative that raises questions about ambition, isolation, and the consequences of human endeavor. The work resonates with themes of existentialism and the fragility of human aspirations.

5. “JG” (2013): A homage to British author J.G. Ballard, this film explores Ballard’s short story “The Voices of Time.” Dean combines footage of Ballard’s Shepperton home with a reading of his text by actor Stephen Dillane. The work serves as a visual and auditory meditation on Ballard’s literary legacy, demonstrating Dean’s ability to engage with other art forms beyond the visual.

Tacita Dean’s body of work showcases a commitment to pushing the boundaries of artistic expression. Through her contemplative explorations of film, nature, and narrative, Dean invites viewers to embark on a journey of introspection and connection with the world around them. Her ability to capture the intangible and make it tangible exemplifies the power of art to transcend the limitations of time and memory.

The ground floor of the link building, added in about 1732 to connect the old house with the new villa. The lead sphinx was made by John Cheere (1709–87)

The ground floor of the link building, added in about 1732 to connect the old house with the new villa. The lead sphinx was made by John Cheere (1709–87)