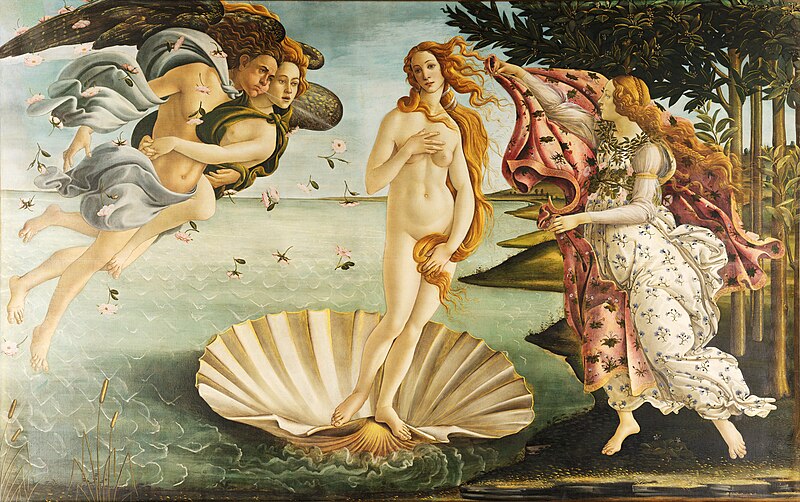

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (c. 1484–1486). Tempera on canvas. 172.5 cm × 278.9 cm (67.9 in × 109.6 in). Uffizi, Florence

“The Birth of Venus” is one of the most iconic and celebrated works of art from the Early Renaissance period. It was created around 1484-1486 and is currently housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy.

Subject and Interpretation: The painting depicts the birth of the goddess Venus (Aphrodite in Greek mythology) as she emerges fully grown from the sea foam, symbolizing her birth as the embodiment of love, beauty, and desire. The mythological scene is inspired by ancient texts, particularly the poem “Theogony” by the ancient Greek poet Hesiod.

Composition: Botticelli masterfully employs a combination of classical and contemporary artistic elements in this work. The central figure of Venus stands tall and elegant, with her body modestly covered by her flowing golden hair and a diaphanous cloth. She is shown in a contrapposto pose, a technique that adds dynamism and naturalism to her figure. On her left, a gentle breeze blows, personified by Zephyr, the god of the west wind, while his lover, Chloris (Flora), awaits Venus with a flower-strewn robe.

The figures’ poses and gestures contribute to the painting’s grace and beauty, which aligns with the Renaissance focus on reviving classical aesthetics and ideals.

Colors and Symbolism: Botticelli’s use of colors is exquisite and adds to the painting’s allure. Soft pastel shades, particularly blues and pinks, dominate the scene, creating a dreamlike ambiance. The painting’s colors, along with the delicate treatment of light and shadow, enhance the ethereal and mythical quality of the subject matter.

Symbolism plays a significant role in “The Birth of Venus.” Besides the symbolism of Venus herself as the goddess of love and beauty, the sea and its foam represent the eternal cycle of creation and transformation. The presence of Zephyr and Chloris symbolizes the winds and the season of spring, connecting the birth of Venus with the rejuvenation of nature and fertility.

Meaning and Influence: Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus” reflects the renewed interest in classical mythology and culture during the Renaissance. The portrayal of mythological subjects became a popular theme among Renaissance artists, who sought to revive the elegance and beauty of ancient Greek and Roman art.

The painting’s enduring popularity lies in its timeless appeal and the way it captures the essence of classical beauty. “The Birth of Venus” has influenced numerous artists throughout history, becoming an essential piece in the understanding of Renaissance art and its cultural significance.

Overall, “The Birth of Venus” is an enchanting masterpiece that embodies the Renaissance spirit, celebrating beauty, grace, and the enduring power of mythological narratives. Its enduring legacy continues to captivate art enthusiasts and remains an integral part of art history to this day.