Lapis lazuli, with its captivating blue hue, has been used in various artworks throughout history. Here, in no particular order, are ten notable artworks that have made exceptional use of lapis lazuli:

“The Last Judgment” by Giotto di Bondone: Giotto’s fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy, showcases the vibrancy of lapis lazuli in its depiction of the heavenly realm. The deep blue background, created using lapis lazuli, emphasizes the celestial atmosphere and heightens the divine presence.

“The Annunciation” by Jan van Eyck: In this masterpiece, housed in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., van Eyck used lapis lazuli to enhance the robes of the Virgin Mary and the angel. The radiant blue provides a striking contrast against the warm tones of the rest of the painting.

The Wilton Diptych”: As previously mentioned, this small diptych, currently housed in the National Gallery, London, incorporates lapis lazuli extensively. The celestial blue background and the clothing of the figures, including the Virgin Mary and angels, showcase the rich and intense blue pigments derived from lapis lazuli

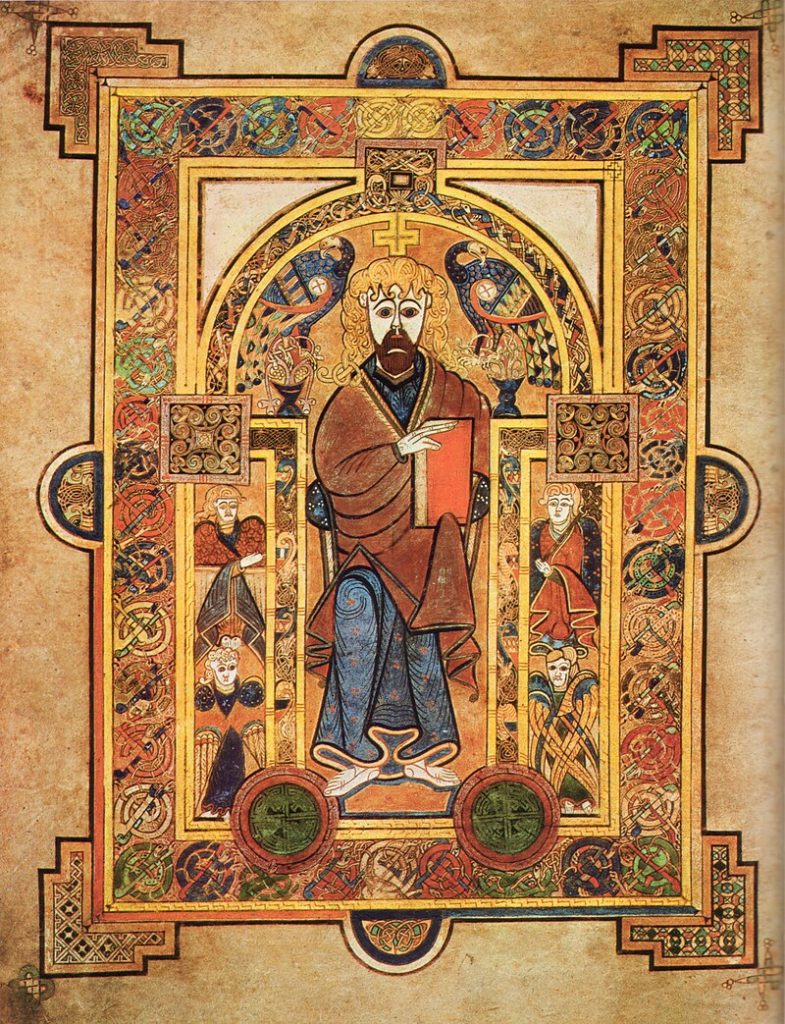

“Book of Kells”: This illuminated manuscript, housed in the Trinity College Library, Dublin, features intricate illustrations adorned with lapis lazuli pigments. The brilliant blue hues lend an ethereal quality to the religious scenes, ornate initials, and elaborate borders.

“The Ghent Altarpiece” by Jan van Eyck: Within this monumental altarpiece, located in St. Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium, lapis lazuli was employed to depict the robes of several figures, including the enthroned Christ and the Virgin Mary. The deep blue conveys their divine status and adds to the overall splendor of the work.

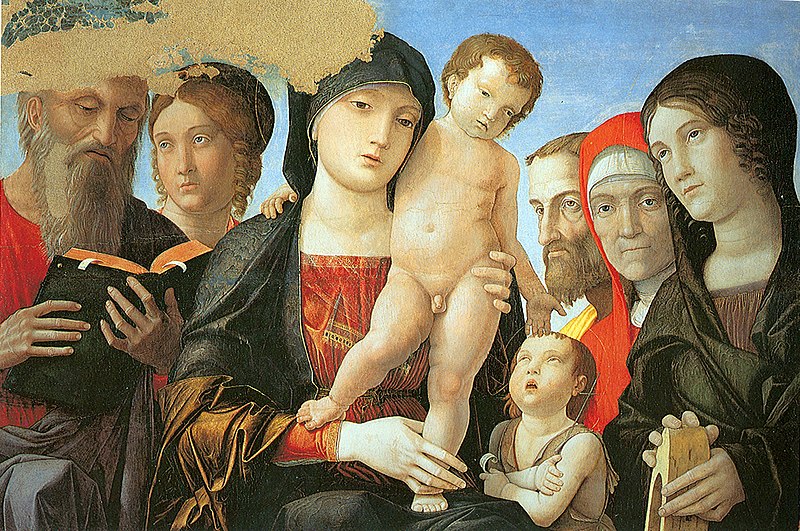

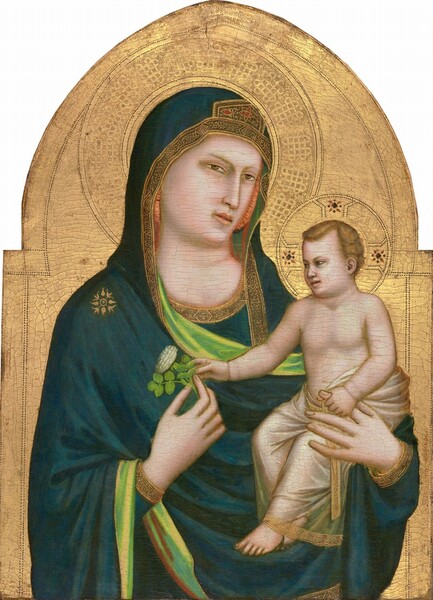

“The Rucellai Madonna” by Duccio di Buoninsegna: This iconic panel painting, found in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, showcases lapis lazuli in the background, creating a celestial atmosphere. The use of the blue pigment highlights the Madonna and Child, drawing attention to their sacred presence.

“The Coronation of the Virgin” by Fra Angelico: Housed in the Louvre Museum, Paris, this altarpiece incorporates lapis lazuli to evoke a sense of heavenly transcendence. The blue background and the angelic figures, embellished with lapis lazuli, create a sublime aura surrounding the central scene.

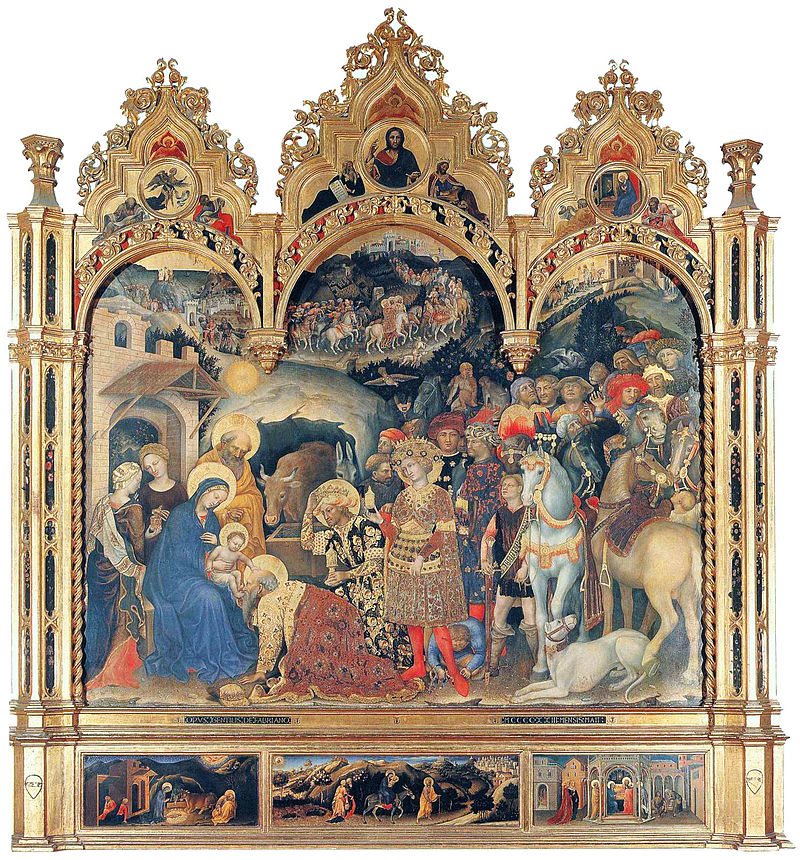

“The Adoration of the Magi” by Gentile da Fabriano: In this magnificent altarpiece, located in the Uffizi Gallery, lapis lazuli is used generously, particularly in the clothing and lavish details. The rich blue pigments heighten the opulence of the scene and symbolize the divine nature of the event.

“The Madonna of Humility” by Masaccio: Within this panel painting, found in the Uffizi Gallery, lapis lazuli is employed to create a radiant blue background, highlighting the Madonna and Child. The blue hue adds depth to the composition and accentuates the contemplative atmosphe

“The Portinari Triptych” by Hugo van der Goes: This altarpiece, housed in the Uffizi Gallery, features lapis lazuli in the background of the central panel and throughout the work. The deep blue hues heighten the spiritual quality of the scene and enhance the overall visual impact

These ten artworks represent a fraction of the rich heritage of lapis lazuli in art history. They demonstrate the exceptional beauty and significance of this precious gemstone, which has played a vital role in conveying