Introduction: Nestled in the heart of Florence, Italy, the Florence Cathedral, also known as the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, stands as a testament to the city’s rich history, architectural prowess, and artistic splendor. In this post, we’ll explore the magnificence of the cathedral, its iconic artworks, and practical details for planning an enriching visit.

History and Architecture: Built over several centuries, with construction commencing in 1296, the Florence Cathedral is a masterpiece of Gothic and Renaissance architecture. Its stunning dome, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi, is an engineering marvel and remains the largest brick dome ever constructed. The intricate façade, adorned with polychrome marble panels, showcases the craftsmanship of generations.

Artistic Treasures Inside: 1. The Last Judgment by Giorgio Vasari:

Ceiling Mural, Georgio Vasari, 1572 and completed by Zuccari 1579

Adorning the interior of the dome, this fresco depicts the final judgment and is a testament to Vasari’s mastery of composition and storytelling.

2. The Baptistry Doors (Gates of Paradise) by Lorenzo Ghiberti:

Baptistry showing Ghiberti’s doors (copies). Originals in museum.

Located on the Baptistery adjacent to the cathedral, these bronze doors are a Renaissance masterpiece, showcasing scenes from the Old Testament with exquisite detail.

3. The Duomo Museum:

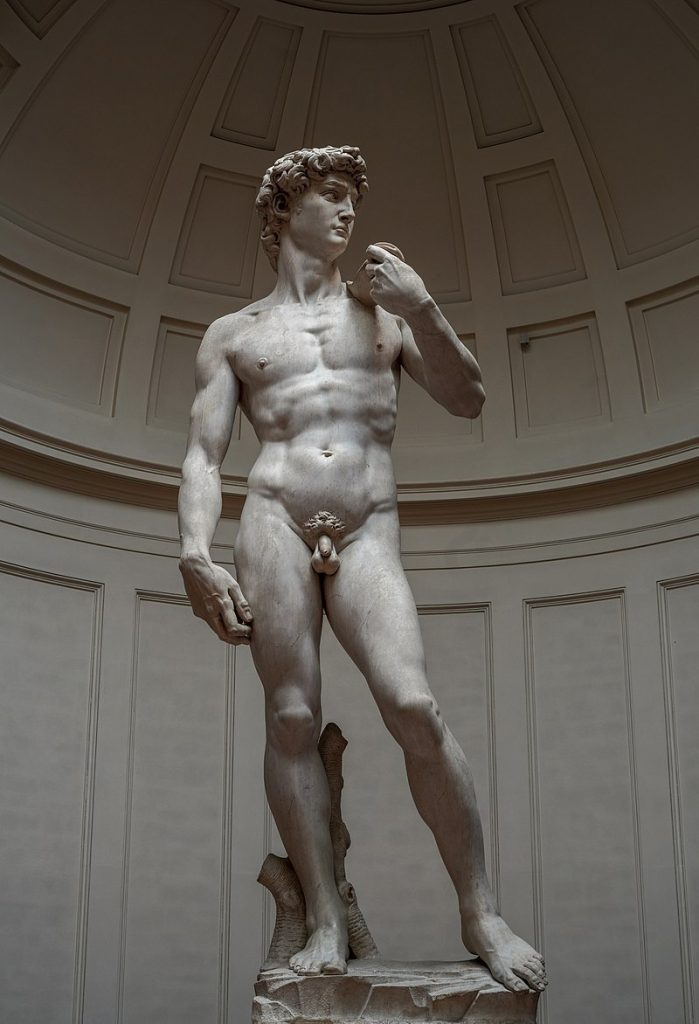

Michelangelo’s Deposition (incorrectly known as the Florence Pieta)

Housing original sculptures from the cathedral, the museum offers insights into the art and history of the Florence Cathedral. Visitors can marvel at Michelangelo’s unfinished Pietà and other precious artifacts.

Opening Times:

- Cathedral: Daily from 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.

- Dome: Daily from 8:30 a.m. to 7 p.m.

- Baptistery: Daily from 8:15 a.m. to 10:15 a.m. and 11:15 a.m. to 7:30 p.m.

- The Duomo Museum: Daily from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. (closed on the first Tuesday of each month)

Planning Your Visit: To make the most of your visit to the Florence Cathedral, consider purchasing a combined ticket that grants access to the cathedral, dome, baptistery, and museum. Be mindful of dress codes, as visitors are expected to dress modestly when entering religious sites. Climbing to the top of the dome provides not only panoramic views of Florence but also a close-up look at the magnificent frescoes.

Experiencing Florence’s Cathedral: Wandering through the grandeur of the Florence Cathedral is a journey through time and artistic innovation. As you marvel at the architectural details, gaze upon masterpieces, and absorb the ambiance of this sacred space, you’ll find yourself immersed in the rich cultural tapestry of Florence. Advance tickets are recommended. Queues can be long especially in summer months and at weekends.

Conclusion: The Florence Cathedral stands as a beacon of art, culture, and spirituality. From its awe-inspiring architecture to the masterpieces housed within, a visit to this iconic landmark promises an enriching experience for art enthusiasts and history lovers alike. Plan your visit thoughtfully, and let the Florence Cathedral unfold its tales of centuries past before your eyes.