with significantly inaccurate anatomy

Lions have held a significant place in English history, symbolizing strength, courage, and nobility. Their presence in heraldry, literature, and the arts underscores their importance in the cultural and political life of England. From the Middle Ages to modern times, lions have been emblematic of power and sovereignty, contributing to the identity and legacy of the nation.

Heraldic Symbolism

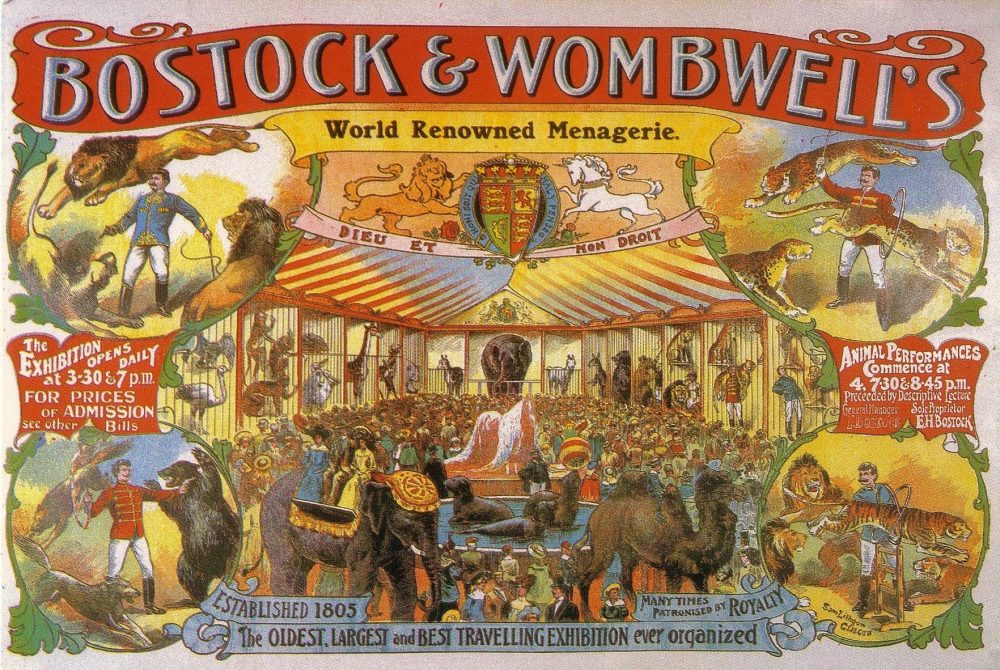

The lion is a dominant motif in English heraldry, often appearing on coats of arms, shields, and banners. Its use as a heraldic symbol dates back to the Norman Conquest in 1066, when William the Conqueror introduced the lion as a representation of royal authority and valor. The lion’s association with the monarchy was solidified during the reign of Richard I, known as Richard the Lionheart, who adopted three lions passant guardant (walking with one forepaw raised) as part of his royal arms. These lions continue to be a central element in the Royal Arms of England.

The lion’s presence in heraldry extended beyond the royal family to the nobility and military, symbolizing bravery, leadership, and martial prowess. The lion rampant (standing on one hind leg with forelegs raised) is another common depiction, signifying ferocity and readiness to defend.

Cultural and Literary Significance

Lions have also played a prominent role in English literature and folklore, often depicted as noble and majestic creatures. In medieval bestiaries, lions were described as the king of beasts, embodying virtues such as strength, courage, and nobility. These attributes made the lion an ideal symbol for the English monarchy and aristocracy.

In literature, lions appear in numerous works, from the medieval epic “Beowulf,” where they symbolize noble qualities, to Shakespeare’s plays, where they often represent power and authority. One of the most famous literary lions is Aslan from C.S. Lewis’s “The Chronicles of Narnia.” Aslan, a Christ-like figure, embodies wisdom, sacrifice, and redemption, reinforcing the lion’s association with noble and virtuous leadership.

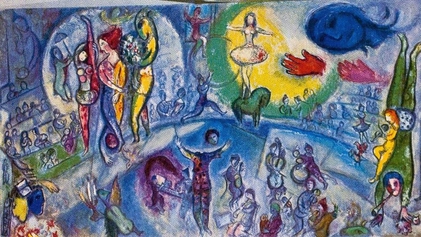

The Lion in Art and Architecture

The lion’s significance is also evident in English art and architecture. Statues and sculptures of lions are common features in public spaces, symbolizing protection and guardianship. The famous lions in Trafalgar Square, designed by Sir Edwin Landseer, are iconic representations that commemorate British naval victories and symbolize the nation’s strength and resilience.

In addition to public monuments, lions are frequently depicted in religious and secular art, often representing the power and sanctity of the institutions they adorn. The lion’s image can be found in churches, palaces, and government buildings, reflecting its pervasive symbolic presence.

Historical Figures and Legends

The lion has been associated with several historical figures and legends, further cementing its importance in English history. Richard the Lionheart’s epithet reflects his reputation for bravery and leadership during the Crusades. His association with the lion reinforced the animal’s symbolic connection to royal authority and military prowess.

Saint Mark, whose symbol is the winged lion, was venerated in England, particularly in Venice, which had strong trading ties with England during the Middle Ages. The lion of Saint Mark, often depicted with a book and a sword, symbolized wisdom and strength, attributes that resonated with English values.

Conclusion

The lion’s significance in English history is profound and multifaceted, encompassing heraldry, literature, art, and architecture. As a symbol of strength, courage, and nobility, the lion has played a crucial role in shaping the cultural and political identity of England. From the medieval period to the present day, the lion remains a powerful emblem of the nation’s heritage and enduring spirit. Its presence in various forms of expression underscores the enduring legacy of this majestic creature in the history and culture of England.

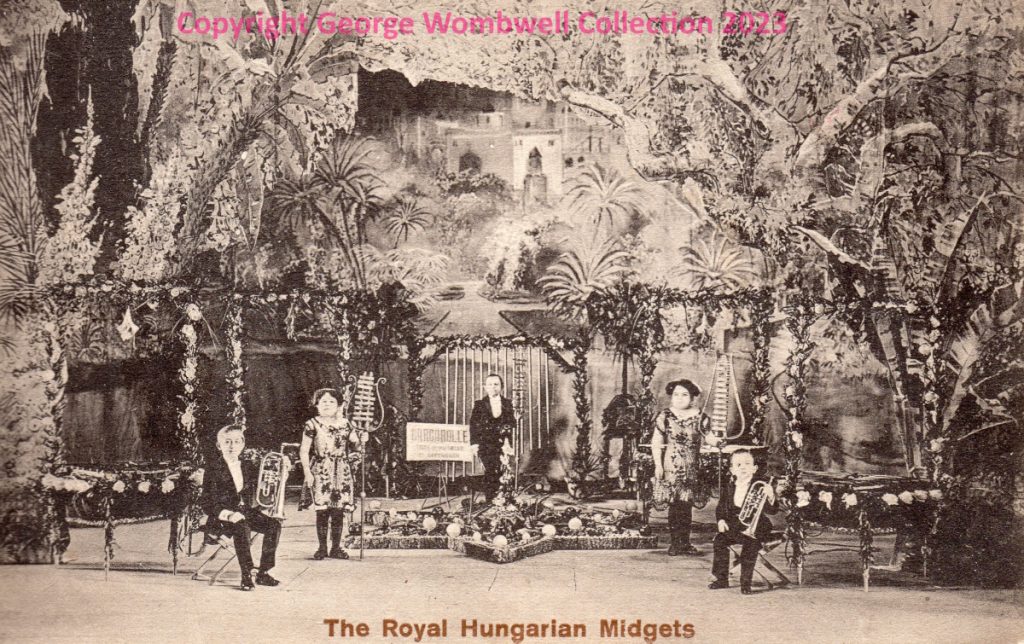

Whilst researching for volume two of the

Whilst researching for volume two of the