Victorian Menageries at Exhibitions

During the Victorian era (1837-1901), exhibitions were a popular form of entertainment and education for the public. These exhibitions showcased various aspects of science, industry, art, and culture, attracting large crowds eager to witness new and exotic discoveries from around the world. One fascinating and recurring attraction at these exhibitions were menageries.

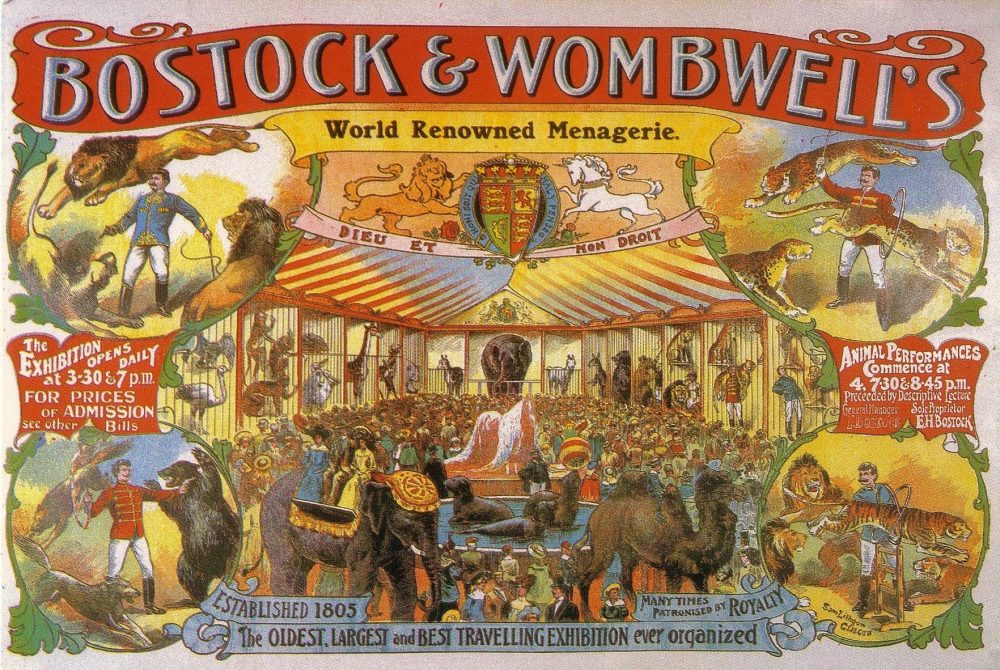

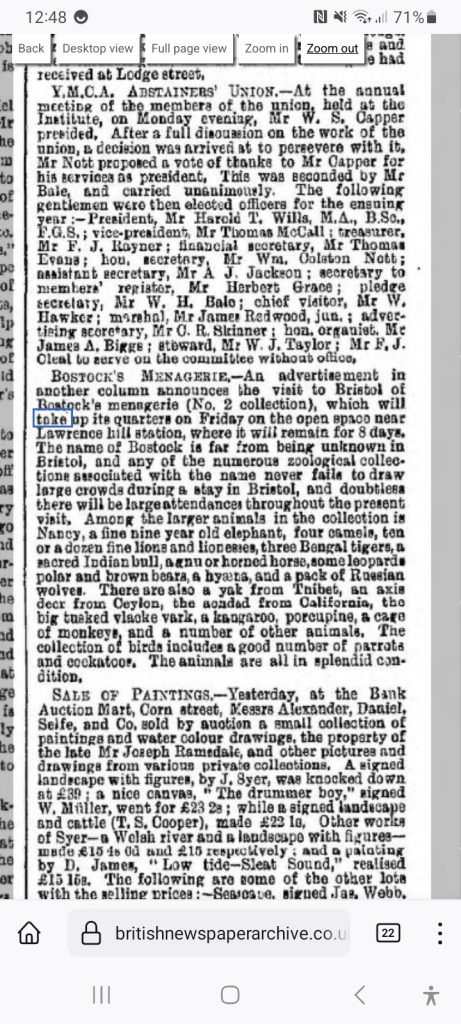

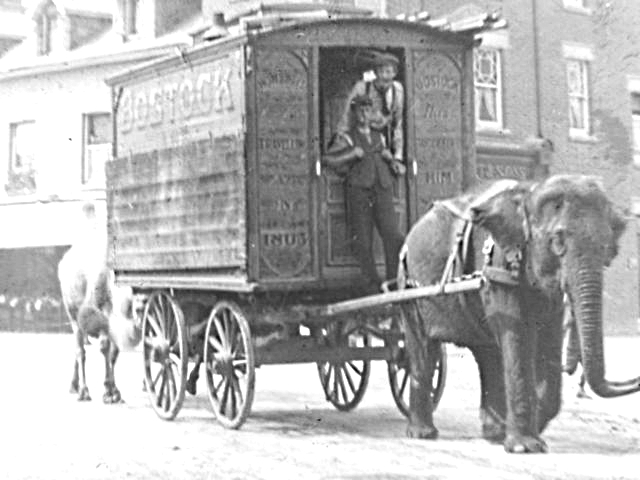

Menageries were collections of live, exotic animals from different parts of the globe, displayed for the public’s amusement and curiosity. They were essentially traveling zoos that brought together a wide variety of creatures that most people in the Victorian era would never have had the chance to see otherwise. Menageries at Victorian exhibitions often included exotic mammals, birds, reptiles, and sometimes even marine life.

Here are some key aspects of menageries that attended Victorian exhibitions:

- Diversity of animals: Menageries boasted an impressive diversity of species, ranging from large elephants, lions, and tigers to colorful birds, monkeys, and reptiles. These collections were often gathered from different continents, representing the wonders of the natural world.

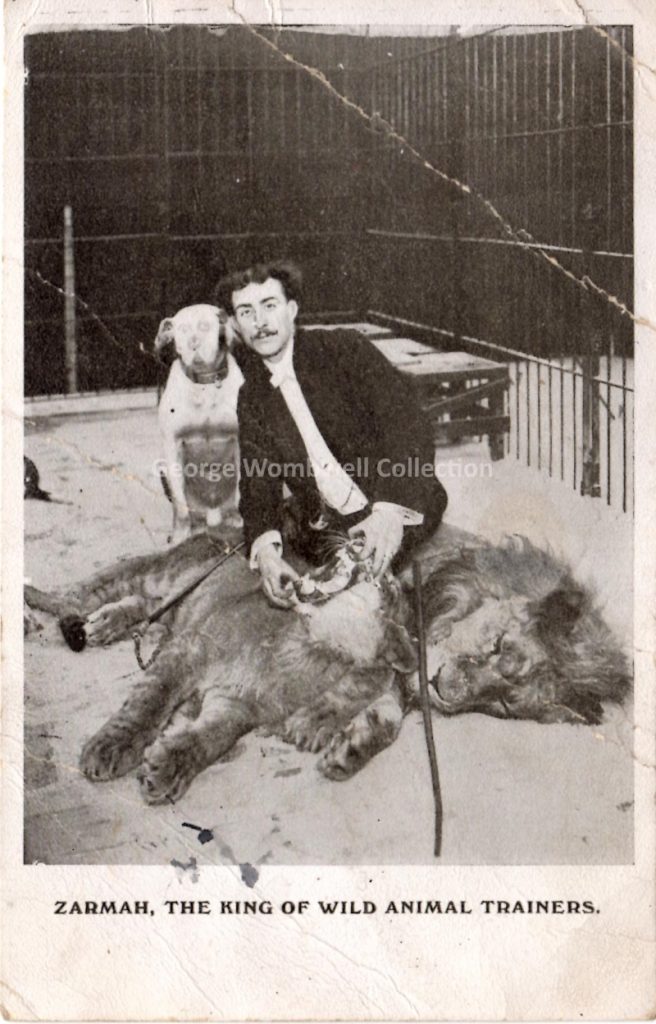

- Sensationalism and entertainment: Menageries were meant to be captivating and awe-inspiring. They appealed to the public’s fascination with the exotic and unknown, and many people attended these exhibitions to marvel at the spectacle of these rare and wild creatures.

- Educational aspects: While the primary goal of menageries was entertainment, they also served an educational purpose. Victorians saw these displays as opportunities to learn about the natural world and expand their knowledge of geography, biology, and wildlife.

- Ethical concerns: While many Victorians found menageries thrilling, they also raised ethical questions about the treatment of the animals. Living conditions in these early zoos were often inadequate, and animals were sometimes subjected to unhealthy environments and mistreatment.

- Influence on society: Menageries and exhibitions played a role in shaping public perceptions and attitudes towards animals and the natural world. They contributed to the development of zoology as a scientific discipline and fostered a growing interest in conservation and animal welfare.

- Legacy and evolution: The concept of menageries continued to evolve over time, leading to the establishment of more modern zoological parks and sanctuaries. These places shifted their focus towards conservation, education, and the overall well-being of animals, moving away from the purely spectacle-oriented approach of Victorian menageries.

One of the most famous examples of a Victorian-era exhibition featuring a menagerie was “The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations” held in London in 1851. This event showcased a wide range of exhibits, including a menagerie featuring live animals from different parts of the world. The inclusion of menageries in such exhibitions was a testament to the allure of exotic wildlife and the thirst for knowledge and adventure that defined the Victorian era.