On show at the Circus Hall of Fame Sarsota, Florid, USA.

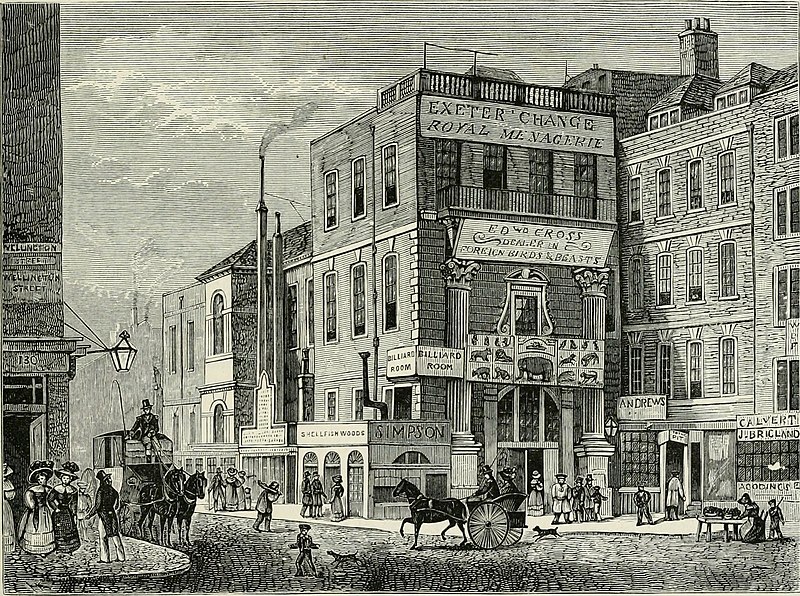

Edward Cross, a notable wild beast merchant of the 19th century, owned and operated the menagerie at Exeter Exchange in London. Among his collection of exotic animals were several lions, and he famously named multiple lions “Wallace.”

Number of Wallace Lions:

It is documented that there were at least three lions named Wallace at different times. Each of these lions gained some degree of fame:

- First Wallace: The original Wallace became quite famous during its time, gaining notoriety for its size and demeanor. This lion was a significant attraction at Exeter Exchange.

- Second Wallace: Following the death of the first Wallace, Cross named another lion Wallace, continuing the legacy and maintaining the public’s interest in his menagerie.

- Third Wallace: A third lion also bore the name Wallace, keeping the tradition alive and ensuring that the name Wallace remained synonymous with the impressive lions of the menagerie.

The practice of reusing the name “Wallace” for successive lions helped build a lasting brand and reputation for Cross’s menagerie, attracting visitors who were familiar with the famed lion by that name. This tradition of naming multiple animals with the same name is not uncommon in the history of menageries and zoos.

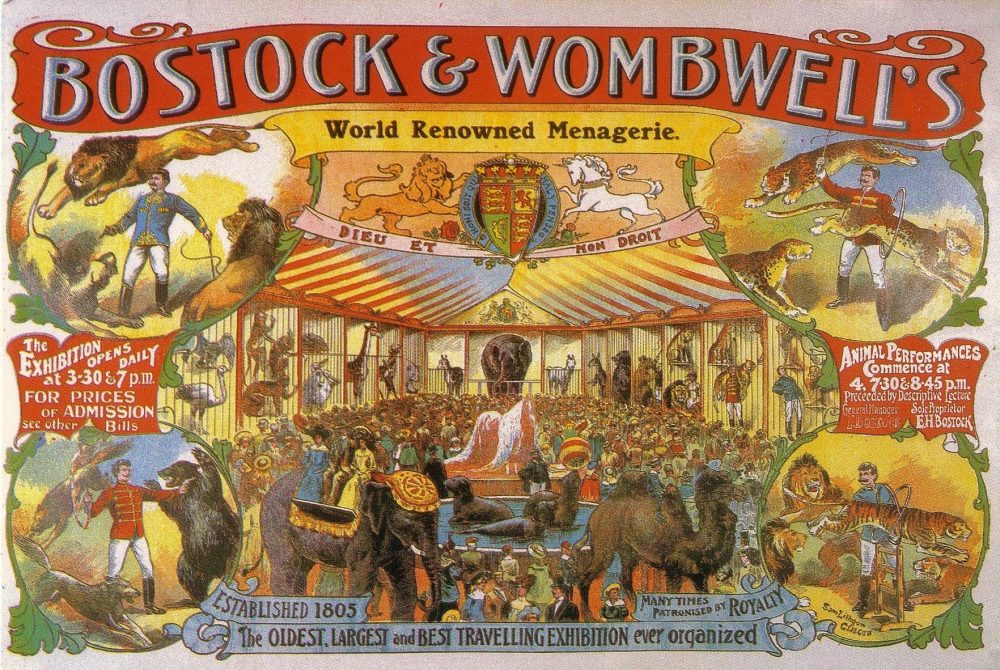

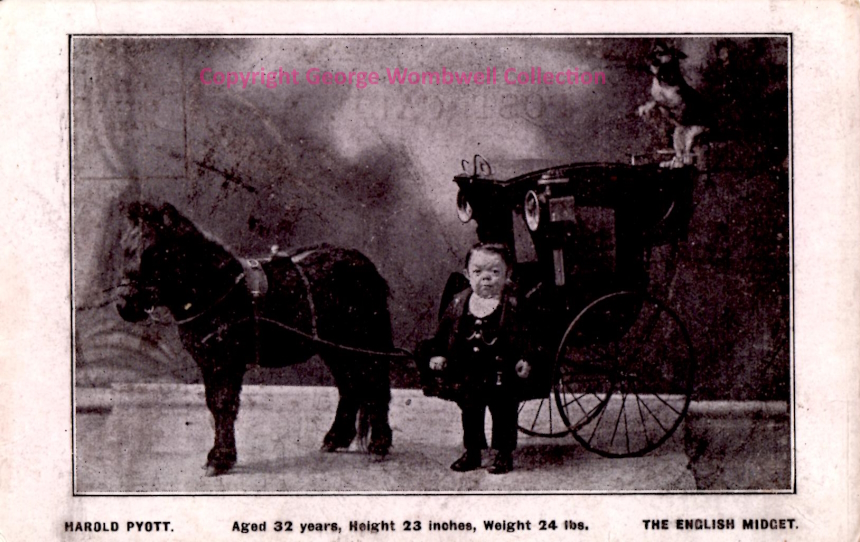

George Wombwell was a prominent British showman and the founder of Wombwell’s Traveling Menagerie, one of the most famous traveling animal shows in the 19th century. His menagerie was renowned for its exotic animals, and among them, a lion named Wallace became particularly famous.

Wallace the Lion

Fame and Legacy:

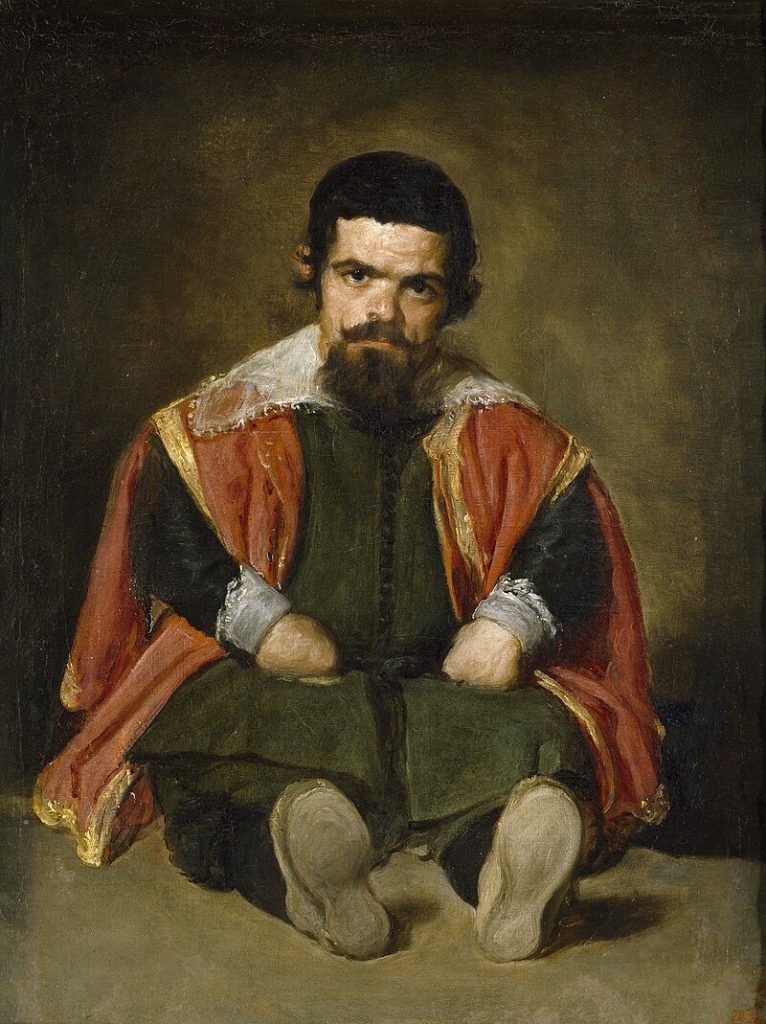

- Exhibition: Wallace was one of the star attractions of Wombwell’s Menagerie. The lion was renowned for his size, strength, and the magnificent mane that became a symbol of the menagerie.

- Docile Nature: Unlike many other lions in captivity at the time, Wallace was known for his relatively docile and gentle nature. This made him particularly popular with the public and allowed for close interactions, which were a major draw for visitors.

- Historical Significance: Wallace was born in captivity in 1812 and became a part of Wombwell’s Menagerie. He lived until 1838, reaching an age of 26 years, which is quite notable for a lion, especially one in captivity during that era.

Impact on Popular Culture:

- Public Attention: Wallace’s fame extended beyond the menagerie itself. His image and stories about him were widely disseminated, making him a household name in 19th-century Britain.

- Literature and Art: Wallace inspired various artistic and literary works, reflecting the public’s fascination with exotic animals and the adventures of traveling menageries.

Legacy of George Wombwell:

- Menagerie Success: George Wombwell’s success with his traveling menagerie was partly due to his ability to create strong public personas for his animals. Wallace the lion was a prime example of this strategy.

- Animal Welfare: Although the standards of animal care were very different in the 19th century compared to today, Wombwell was known for his relatively good treatment of his animals, which contributed to their longevity and the success of his menagerie.

Conclusion:

George Wombwell’s lion, Wallace, remains one of the most famous lions in the history of traveling menageries. Wallace’s reputation for being a magnificent and gentle lion made him a star attraction and helped cement George Wombwell’s legacy as a leading showman of his time. The story of Wallace highlights the public’s enduring fascination with exotic animals and the rich history of animal exhibitions in the 19th century.

However, the Wallace depicted above was from the USA, and, according to the card, was from the Wombwell and Bostock Wold Animal Show. Reported to have killed 3 of its trainers and had to be ‘executed’.

It was Frank Bostock that went to the USA in the late 1800s and successfully traveled the country with his Wild Animal Show. He also had a permanent site on Coney Island, New York.

Frank Bostock and His Menagerie in New York

Introduction

Frank C. Bostock, known as the “Animal King,” was a pioneering figure in the world of traveling menageries and animal shows. Originating from a family deeply entrenched in the circus and menagerie business in the UK, Bostock expanded his operations internationally, achieving remarkable success in New York in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Early Life and Background

Born in 1866 in England, Frank Bostock was part of the famous Bostock and Wombwell menagerie family. From a young age, he was immersed in the world of exotic animals and show business. Frank eventually branched out to create his own menagerie, distinct from his family’s legacy, which would go on to become a global sensation.

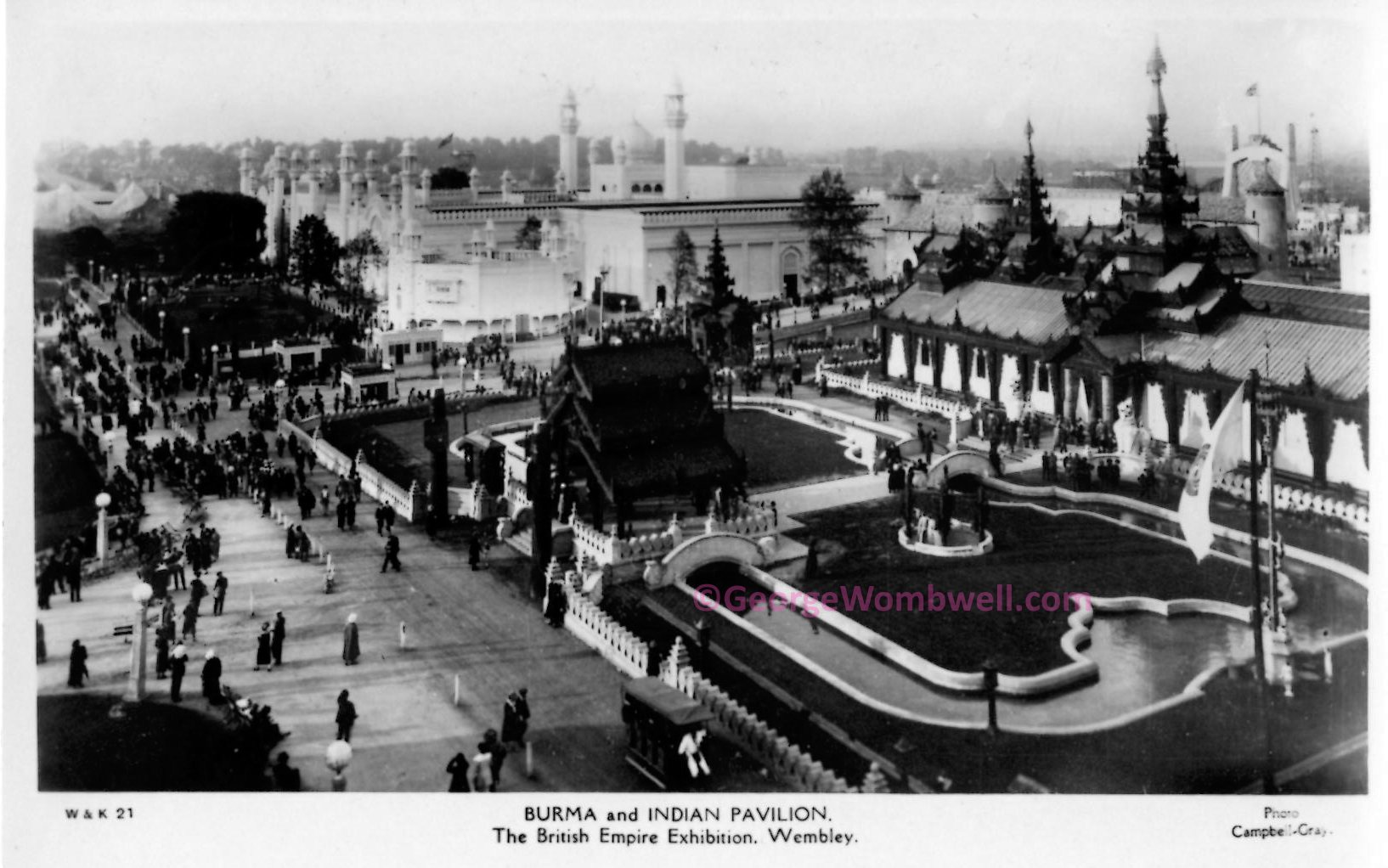

Arrival in New York

In the early 1890s, Frank Bostock brought his menagerie to the United States, where he quickly made a name for himself. New York, with its burgeoning entertainment industry and appetite for spectacle, provided the perfect setting for Bostock’s grand exhibitions.

Bostock’s Menagerie

- Exotic Animals and Training:

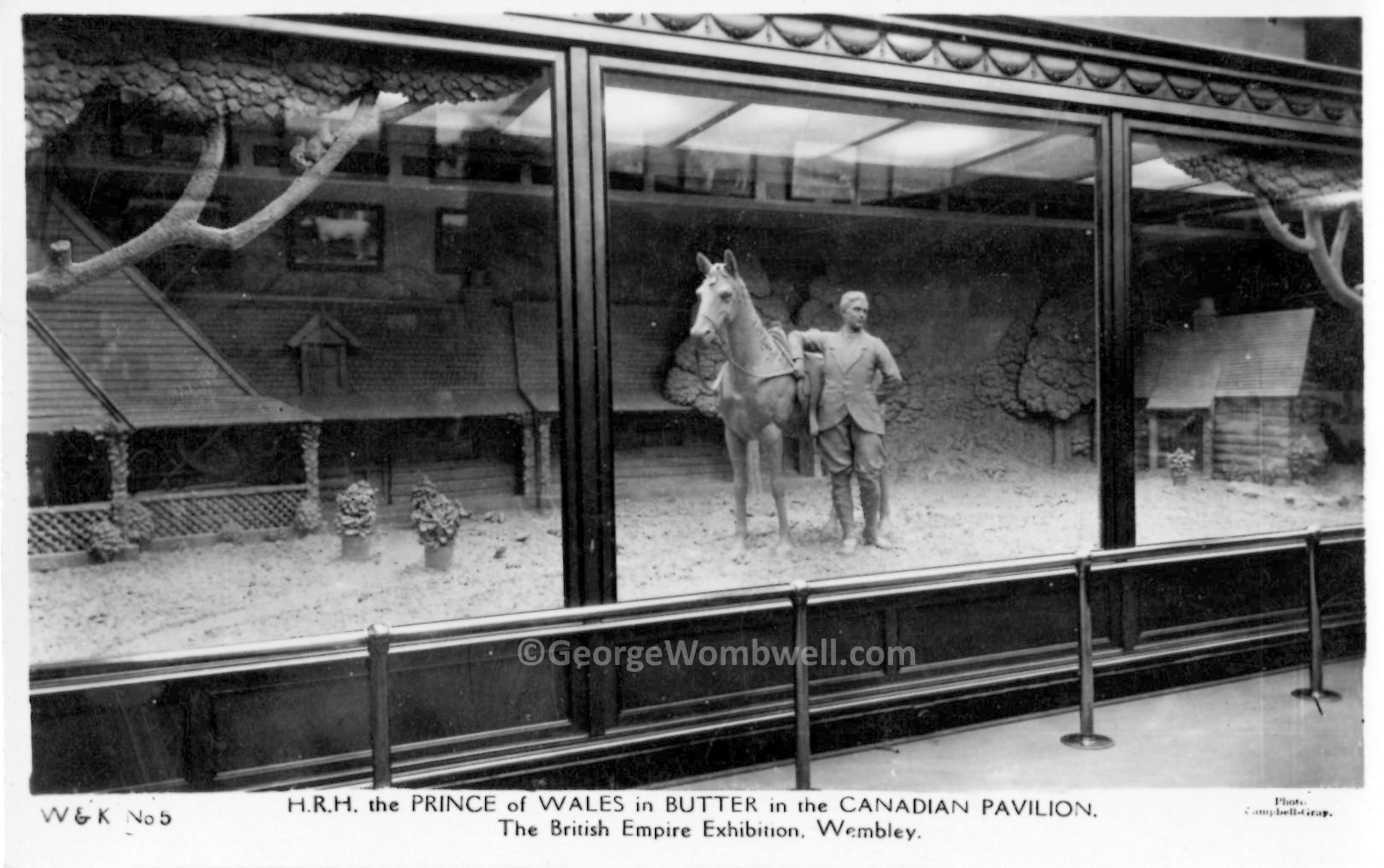

- Diverse Collection: Bostock’s menagerie featured a wide array of exotic animals, including lions, tigers, elephants, bears, and more. His collection was known for its variety and the healthy condition of the animals.

- Innovative Training: Frank Bostock was renowned for his innovative and humane training techniques. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he emphasized positive reinforcement and developed a deep understanding of animal behavior, which allowed him to perform complex and engaging shows.

- Spectacular Shows:

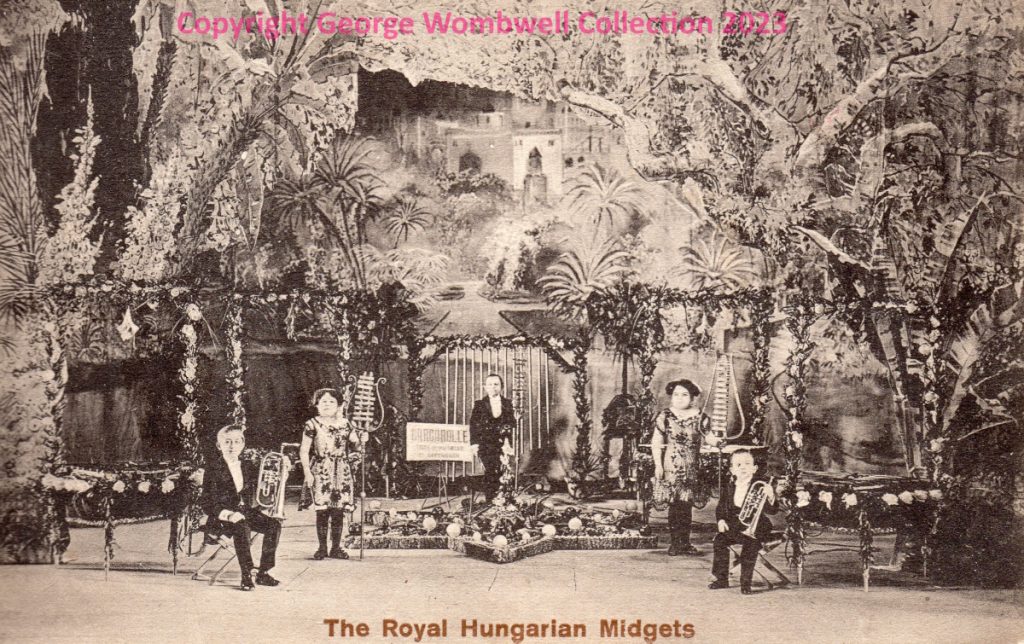

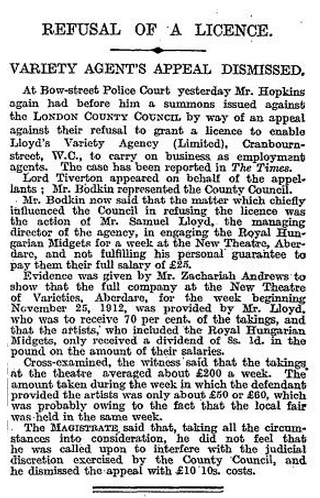

- Public Exhibitions: Bostock’s shows were a mix of education and entertainment. He showcased not only the animals’ natural behaviors but also their trained abilities. This approach captivated audiences and made his shows a must-see attraction in New York.

- The Arena: In 1903, Bostock opened a permanent exhibition space known as Bostock’s Arena at Coney Island. The arena was a state-of-the-art facility designed to house his extensive menagerie and host daily shows. It quickly became one of Coney Island’s premier attractions.

- Notable Performances and Incidents:

- Major Public Draw: Bostock’s performances included daring acts such as lion taming, tiger training, and elephant performances. His shows were characterized by their dramatic flair and the close bond he shared with his animals.

- Fire at Dreamland: In 1911, a tragic fire at Dreamland amusement park, where Bostock had his animals, resulted in significant losses. Many of the animals perished in the fire, marking a somber moment in his career.

Impact on New York and Legacy

- Influence on Animal Shows:

- Setting Standards: Bostock set new standards for animal care and training, influencing future generations of trainers and entertainers. His methods were studied and emulated by many in the industry.

- Public Perception: He played a significant role in changing the public perception of animal exhibitions from mere curiosities to respected forms of entertainment and education.

- Cultural Contributions:

- Entertainment Industry: Bostock’s success in New York contributed to the growth of the entertainment industry, particularly in Coney Island, which became a hub for amusement parks and attractions.

- Animal Welfare Awareness: His humane approach to animal training brought attention to the importance of animal welfare, laying the groundwork for future improvements in the treatment of performing animals.

- Enduring Fame:

- Publications and Media: Bostock’s life and career were chronicled in various publications, and his menagerie was frequently covered in the media. His fame extended beyond the United States, cementing his legacy as a global showman.

Conclusion

Frank Bostock’s tenure in New York marked a significant chapter in the history of traveling menageries and animal exhibitions. Through his innovative approach to animal training and showmanship, Bostock captivated audiences and set new standards for the industry. His legacy as the “Animal King” endures, reflecting his contributions to entertainment, animal welfare, and cultural history.