Verso:

‘on Great North Road 1903’

‘McAlpine’

Pencil: ‘Noble Horse’

Verso:

‘on Great North Road 1903’

‘McAlpine’

Pencil: ‘Noble Horse’

Lions have held a significant place in English history, symbolizing strength, courage, and nobility. Their presence in heraldry, literature, and the arts underscores their importance in the cultural and political life of England. From the Middle Ages to modern times, lions have been emblematic of power and sovereignty, contributing to the identity and legacy of the nation.

The lion is a dominant motif in English heraldry, often appearing on coats of arms, shields, and banners. Its use as a heraldic symbol dates back to the Norman Conquest in 1066, when William the Conqueror introduced the lion as a representation of royal authority and valor. The lion’s association with the monarchy was solidified during the reign of Richard I, known as Richard the Lionheart, who adopted three lions passant guardant (walking with one forepaw raised) as part of his royal arms. These lions continue to be a central element in the Royal Arms of England.

The lion’s presence in heraldry extended beyond the royal family to the nobility and military, symbolizing bravery, leadership, and martial prowess. The lion rampant (standing on one hind leg with forelegs raised) is another common depiction, signifying ferocity and readiness to defend.

Lions have also played a prominent role in English literature and folklore, often depicted as noble and majestic creatures. In medieval bestiaries, lions were described as the king of beasts, embodying virtues such as strength, courage, and nobility. These attributes made the lion an ideal symbol for the English monarchy and aristocracy.

In literature, lions appear in numerous works, from the medieval epic “Beowulf,” where they symbolize noble qualities, to Shakespeare’s plays, where they often represent power and authority. One of the most famous literary lions is Aslan from C.S. Lewis’s “The Chronicles of Narnia.” Aslan, a Christ-like figure, embodies wisdom, sacrifice, and redemption, reinforcing the lion’s association with noble and virtuous leadership.

The lion’s significance is also evident in English art and architecture. Statues and sculptures of lions are common features in public spaces, symbolizing protection and guardianship. The famous lions in Trafalgar Square, designed by Sir Edwin Landseer, are iconic representations that commemorate British naval victories and symbolize the nation’s strength and resilience.

In addition to public monuments, lions are frequently depicted in religious and secular art, often representing the power and sanctity of the institutions they adorn. The lion’s image can be found in churches, palaces, and government buildings, reflecting its pervasive symbolic presence.

The lion has been associated with several historical figures and legends, further cementing its importance in English history. Richard the Lionheart’s epithet reflects his reputation for bravery and leadership during the Crusades. His association with the lion reinforced the animal’s symbolic connection to royal authority and military prowess.

Saint Mark, whose symbol is the winged lion, was venerated in England, particularly in Venice, which had strong trading ties with England during the Middle Ages. The lion of Saint Mark, often depicted with a book and a sword, symbolized wisdom and strength, attributes that resonated with English values.

The lion’s significance in English history is profound and multifaceted, encompassing heraldry, literature, art, and architecture. As a symbol of strength, courage, and nobility, the lion has played a crucial role in shaping the cultural and political identity of England. From the medieval period to the present day, the lion remains a powerful emblem of the nation’s heritage and enduring spirit. Its presence in various forms of expression underscores the enduring legacy of this majestic creature in the history and culture of England.

On show at the Circus Hall of Fame Sarsota, Florid, USA.

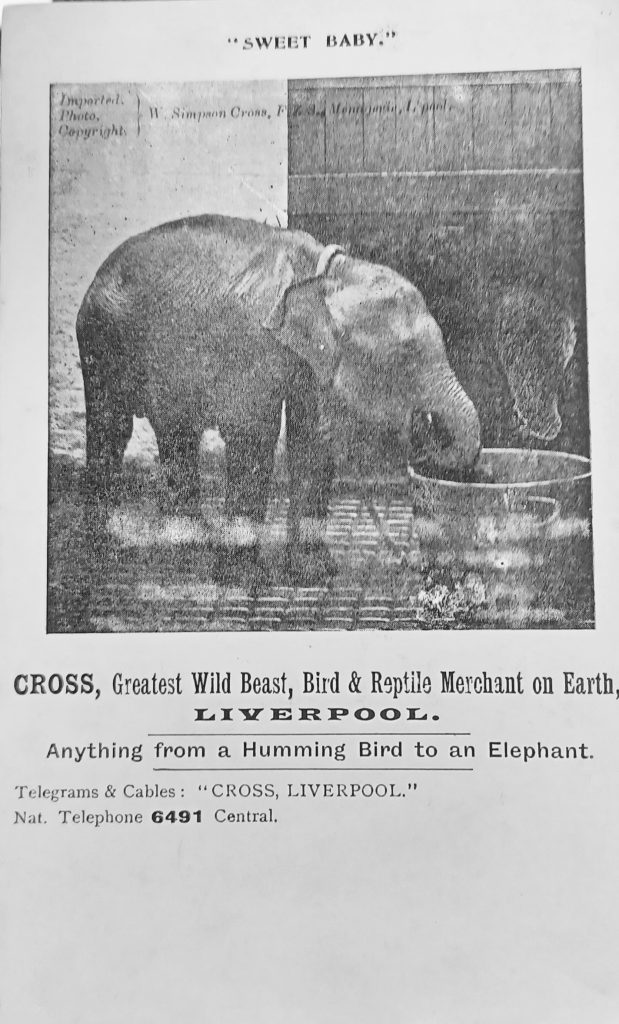

Edward Cross, a notable wild beast merchant of the 19th century, owned and operated the menagerie at Exeter Exchange in London. Among his collection of exotic animals were several lions, and he famously named multiple lions “Wallace.”

Number of Wallace Lions:

It is documented that there were at least three lions named Wallace at different times. Each of these lions gained some degree of fame:

The practice of reusing the name “Wallace” for successive lions helped build a lasting brand and reputation for Cross’s menagerie, attracting visitors who were familiar with the famed lion by that name. This tradition of naming multiple animals with the same name is not uncommon in the history of menageries and zoos.

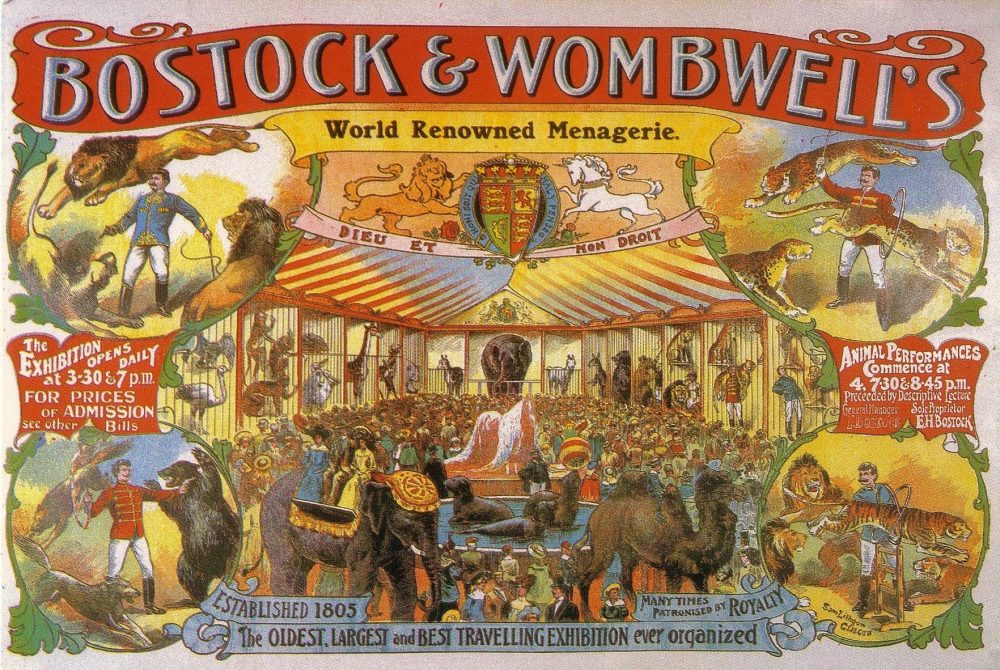

George Wombwell was a prominent British showman and the founder of Wombwell’s Traveling Menagerie, one of the most famous traveling animal shows in the 19th century. His menagerie was renowned for its exotic animals, and among them, a lion named Wallace became particularly famous.

Fame and Legacy:

George Wombwell’s lion, Wallace, remains one of the most famous lions in the history of traveling menageries. Wallace’s reputation for being a magnificent and gentle lion made him a star attraction and helped cement George Wombwell’s legacy as a leading showman of his time. The story of Wallace highlights the public’s enduring fascination with exotic animals and the rich history of animal exhibitions in the 19th century.

However, the Wallace depicted above was from the USA, and, according to the card, was from the Wombwell and Bostock Wold Animal Show. Reported to have killed 3 of its trainers and had to be ‘executed’.

It was Frank Bostock that went to the USA in the late 1800s and successfully traveled the country with his Wild Animal Show. He also had a permanent site on Coney Island, New York.

Frank C. Bostock, known as the “Animal King,” was a pioneering figure in the world of traveling menageries and animal shows. Originating from a family deeply entrenched in the circus and menagerie business in the UK, Bostock expanded his operations internationally, achieving remarkable success in New York in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Born in 1866 in England, Frank Bostock was part of the famous Bostock and Wombwell menagerie family. From a young age, he was immersed in the world of exotic animals and show business. Frank eventually branched out to create his own menagerie, distinct from his family’s legacy, which would go on to become a global sensation.

In the early 1890s, Frank Bostock brought his menagerie to the United States, where he quickly made a name for himself. New York, with its burgeoning entertainment industry and appetite for spectacle, provided the perfect setting for Bostock’s grand exhibitions.

Frank Bostock’s tenure in New York marked a significant chapter in the history of traveling menageries and animal exhibitions. Through his innovative approach to animal training and showmanship, Bostock captivated audiences and set new standards for the industry. His legacy as the “Animal King” endures, reflecting his contributions to entertainment, animal welfare, and cultural history.

This postcard is pre 1912. William Cross, grandson of Edward ran the menagerie until a fire destroyed it in 1912.

In the annals of history, certain figures emerge whose lives are as captivating as the stories they inhabit. One such individual is Edward Cross, whose remarkable journey as a wild beast merchant left an indelible mark on the world of entertainment in the 19th century.

The Early Years

Edward Cross was born in England in the early 1800s, during a time when the allure of the exotic and the unknown captivated the imaginations of people across the globe. From a young age, Cross exhibited a keen interest in the natural world, particularly in the magnificent creatures that roamed the earth’s far-flung corners.

A Merchant of Marvels

As he matured, Cross channeled his passion for wildlife into a burgeoning business venture: the trade of wild animals. In an era when exotic animals were coveted symbols of wealth and power, Cross carved out a niche for himself as a purveyor of rare and exotic beasts.

The Menagerie Takes Shape

Cross’s endeavors led him to establish a menagerie—an extravagant collection of wild animals from around the world. From lions and tigers to elephants and giraffes, his menagerie boasted an astonishing array of creatures that dazzled audiences with their beauty and ferocity.

The Circus Connection

Recognizing the potential for spectacle and entertainment, Cross partnered with circus impresarios to showcase his menagerie to the masses. Together, they transformed the presentation of wild animals into a mesmerizing spectacle, complete with daring feats and awe-inspiring performances.

Challenges and Triumphs

Cross’s journey as a wild beast merchant was not without its challenges. From logistical hurdles to the ethical considerations surrounding the captivity of wild animals, he faced myriad obstacles along the way. Yet, through sheer determination and ingenuity, he persevered, leaving an indelible legacy on the world of entertainment.

Legacy and Impact

Edward Cross’s legacy endures as a testament to the boundless human spirit and our insatiable curiosity about the natural world. Though the era of wild beast merchants may have passed, the allure of exotic animals and the spectacle of the circus continue to captivate audiences to this day.

Conclusion

In the colorful tapestry of history, figures like Edward Cross shine as beacons of curiosity, ambition, and adventure. His journey as a wild beast merchant stands as a testament to the power of passion and perseverance in the pursuit of one’s dreams. As we reflect on his remarkable story, we are reminded of the enduring magic of the natural world and the timeless allure of the circus.

I. Introduction

Travelling menageries were a prominent feature of British society during the 19th century, offering audiences the opportunity to encounter exotic animals from around the world. This literature review(without references) explores the multifaceted impacts of travelling menageries on British society, focusing on their social, cultural, and economic dimensions.

II. Historical Background of Travelling Menageries

Travelling menageries emerged in Britain during the late 18th century, capitalizing on public fascination with exotic wildlife and the growing interest in natural history. These exhibitions featured a diverse array of animals, ranging from elephants and lions to monkeys and birds, and were often accompanied by spectacle and entertainment. Menageries toured cities and towns across the country, drawing crowds eager to witness the wonders of the natural world.

III. Social Impacts of Travelling Menageries

Menagerie exhibitions provided a form of entertainment accessible to people of all social classes, offering a rare opportunity for individuals to interact with exotic animals. Working-class audiences, in particular, were drawn to menageries as a means of escape from the drudgery of daily life. However, debates surrounding animal welfare and ethical treatment also emerged, sparking discussions about humanity’s relationship with the natural world.

IV. Cultural Impacts of Travelling Menageries

Travelling menageries played a significant role in shaping British culture during the 19th century, influencing artistic expressions, literary works, and popular imagination. Artists and writers drew inspiration from menagerie exhibitions, incorporating exotic animals and scenes into their creations. Moreover, menageries contributed to the construction of narratives of exoticism and colonialism, reflecting broader cultural attitudes towards the “other” and the fascination with the unknown.

V. Economic Impacts of Travelling Menageries

As commercial enterprises, travelling menageries had a substantial economic impact on British society. Menagerie owners operated lucrative businesses, charging admission fees and selling souvenirs to patrons. The tours of menageries also provided economic opportunities for local communities, stimulating commerce and attracting visitors to towns and cities. However, the profitability of menageries was often precarious, with financial challenges leading to the eventual decline of the industry in the late 19th century.

VI. Methodological Approaches in Studying Travelling Menageries

Scholarly research on travelling menageries employs a variety of methodological approaches, including archival research, historical analysis, and cultural studies. Primary sources such as newspaper articles, diaries, and advertisements provide valuable insights into the experiences of audiences and the operations of menageries. However, researchers must navigate challenges such as biased representations and gaps in the historical record when studying this topic.

VII. Themes and Trends in the Literature

Existing scholarship on travelling menageries reveals several recurring themes and trends. Scholars have explored the intersections of entertainment, education, and exploitation in menagerie exhibitions, as well as the broader implications for understanding human-animal relationships. However, gaps in the literature persist, particularly regarding the perspectives of marginalized groups and the long-term legacies of menageries on British society.

VIII. Conclusion

Travelling menageries left a lasting imprint on 19th-century British society, influencing social interactions, cultural representations, and economic dynamics. Despite their eventual decline, menageries continue to fascinate scholars and enthusiasts alike, offering a window into a bygone era of exploration and spectacle. By examining the social, cultural, and economic impacts of travelling menageries, we gain valuable insights into the complexities of human-animal relations and the intersections of entertainment, commerce, and culture in the Victorian era.

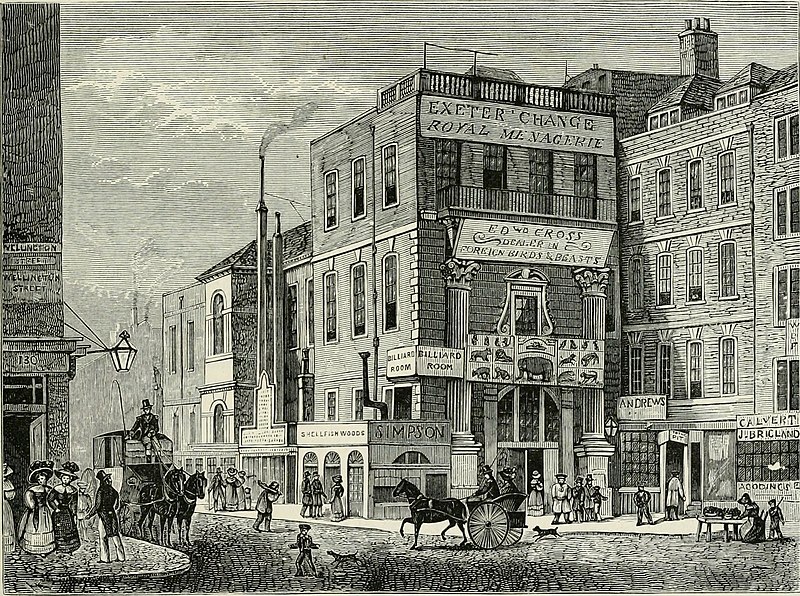

Tucked away in the annals of numismatic history lies a captivating chapter centered around the Exeter Exchange tokens—a series of coin-like tokens that once circulated in the bustling streets of London during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. These tokens, minted for use at the Exeter Exchange, are not just pieces of metal; they represent a convergence of commerce, culture, and craftsmanship.

The Exeter Exchange:

Located in the heart of London’s West End, the Exeter Exchange was a prominent commercial and social hub during its heyday. Built in the early 17th century, it housed a menagerie, shops, and a coffeehouse, attracting visitors from all walks of life. The Exchange was not only a place of business but also a venue for entertainment and enlightenment—a microcosm of London’s vibrant spirit.

The Tokens’ Purpose:

Amidst the bustling activity of the Exeter Exchange, traditional currency often proved insufficient for transactions. To address this challenge, the proprietors of the Exchange issued their own tokens—small, circular pieces of metal bearing inscriptions and images that represented various denominations of currency. These tokens served as a convenient and reliable medium of exchange within the confines of the Exchange, facilitating commerce and fostering a sense of community among patrons.

Design and Symbolism:

What sets Exeter Exchange tokens apart is their intricate design and rich symbolism. Crafted by skilled artisans, these tokens feature a variety of motifs, including depictions of exotic animals from the menagerie, architectural elements of the Exchange building, and allegorical figures representing commerce and prosperity. Each token is a miniature work of art, reflecting the cultural and aesthetic sensibilities of its time.

Historical Significance:

Beyond their aesthetic appeal, Exeter Exchange tokens hold significant historical value. They provide valuable insights into the economic, social, and cultural dynamics of 18th and 19th-century London. Through their study, historians and numismatists can trace patterns of trade, explore the evolution of urban spaces, and uncover the everyday experiences of individuals living in the bustling metropolis.

Legacy and Collectibility:

Today, Exeter Exchange tokens are highly sought after by collectors and enthusiasts of numismatics. Their rarity, historical significance, and artistic merit make them prized additions to private collections and museum exhibits alike. Each token serves as a tangible link to a bygone era, inviting us to delve into the stories they hold and the worlds they represent.

Preserving the Past:

As we marvel at the beauty and complexity of Exeter Exchange tokens, we also recognize the importance of preserving them for future generations. These tokens are more than just relics; they are windows into our shared heritage, reminding us of the ingenuity, creativity, and resilience of those who came before us.

In conclusion, the story of Exeter Exchange tokens is a testament to the enduring legacy of London’s past. As we reflect on their significance, let us remember the vibrant history they represent and the invaluable lessons they impart about the intersection of commerce, culture, and community in the heart of the city.

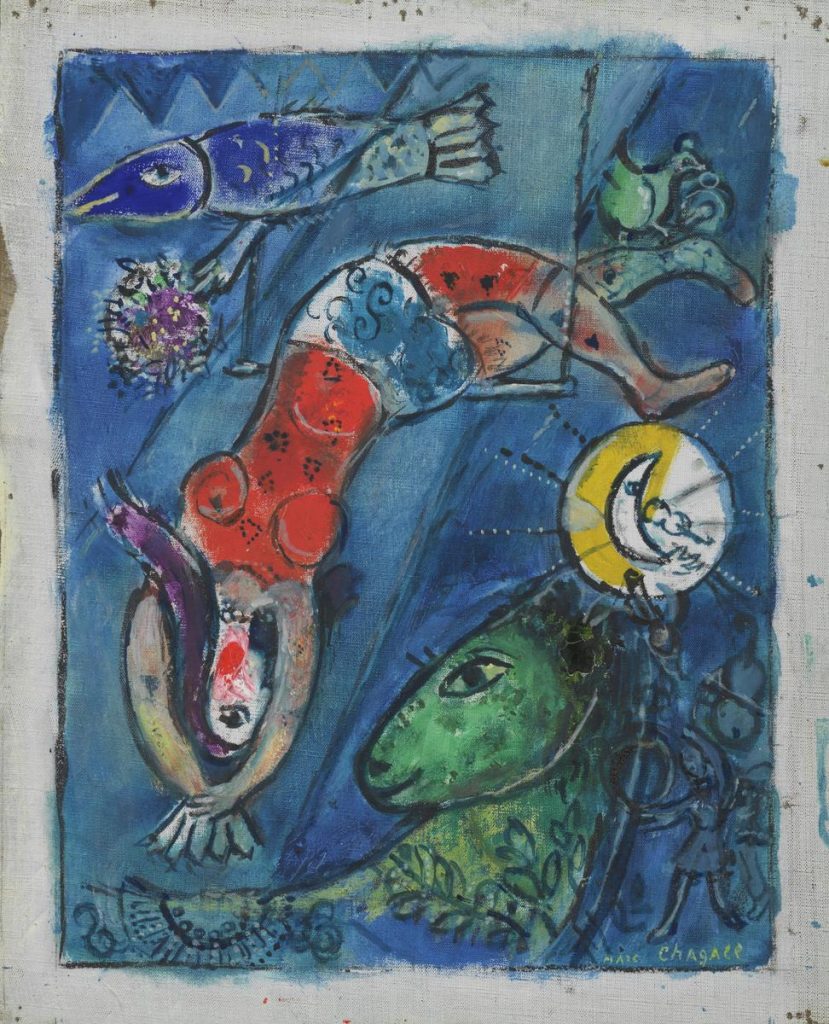

Marc Chagal, Le Grand Cirque, 1956, Oil on canvas, Private Collection

Marc Chagal, The Horse Rider 1949-53 Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

Marc Chagal, Circus Horse 1964

In the colorful tapestry of entertainment history, Frank Bostock’s menagerie stands out as a fascinating chapter that brought the exotic wonders of the animal kingdom to the doorsteps of audiences. Born in 1866, Frank Bostock was a showman and menagerist who created a traveling spectacle that captivated the imaginations of people across continents.

Bostock’s journey into the world of menageries began at a young age. His fascination with animals and a keen sense of showmanship led him to establish his own menagerie, showcasing a diverse collection of creatures from every corner of the globe. Bostock’s vision was not just about displaying exotic animals but creating an immersive experience that transported spectators to far-off lands.

What set Bostock apart was his mobile menagerie – a traveling caravan of wonders that brought the allure of the wild to both urban centers and rural areas. From lions and tigers to elephants and exotic birds, the menagerie featured a breathtaking array of creatures. This traveling spectacle became a cultural phenomenon, providing a taste of the exotic to audiences who might never have the chance to see such animals otherwise.

Bostock’s menagerie wasn’t merely about entertainment; it also served an educational purpose. His shows often included informative talks about the habits, habitats, and characteristics of the animals on display. Bostock sought to cultivate a sense of wonder and respect for the natural world, fostering a connection between people and the creatures that shared the planet.

Bostock’s menagerie gained royal approval when he presented his traveling show to King Edward VII, further solidifying its prestige. Beyond the shores of England, Bostock expanded his menagerie empire internationally. The success of his shows in the United States and Australia attested to the universal appeal of his carefully curated exhibits.

Running a traveling menagerie posed numerous challenges. Animal welfare concerns were raised, and Bostock faced criticism for the conditions in which the animals were kept. However, it’s important to contextualize these issues within the historical understanding of animal care during the time. Bostock, in his era, was at the forefront of popularizing and showcasing wildlife.

Frank Bostock’s menagerie left an indelible mark on the history of entertainment. His innovative approach to combining education with spectacle laid the groundwork for future zoos and wildlife exhibitions. The legacy of Bostock’s menagerie endures in the collective memory of those who experienced the thrill of encountering exotic animals in the midst of their everyday lives.

In the grand tapestry of showmanship, Frank Bostock’s menagerie remains a vivid thread that weaves together the realms of entertainment, education, and wildlife appreciation. Bostock’s traveling spectacle brought the wild to the urban and rural landscapes, leaving an imprint on the cultural fabric of the times. While the methods and ethical standards of animal exhibitions have evolved, Bostock’s menagerie remains a fascinating chapter in the history of human fascination with the wonders of the animal kingdom.

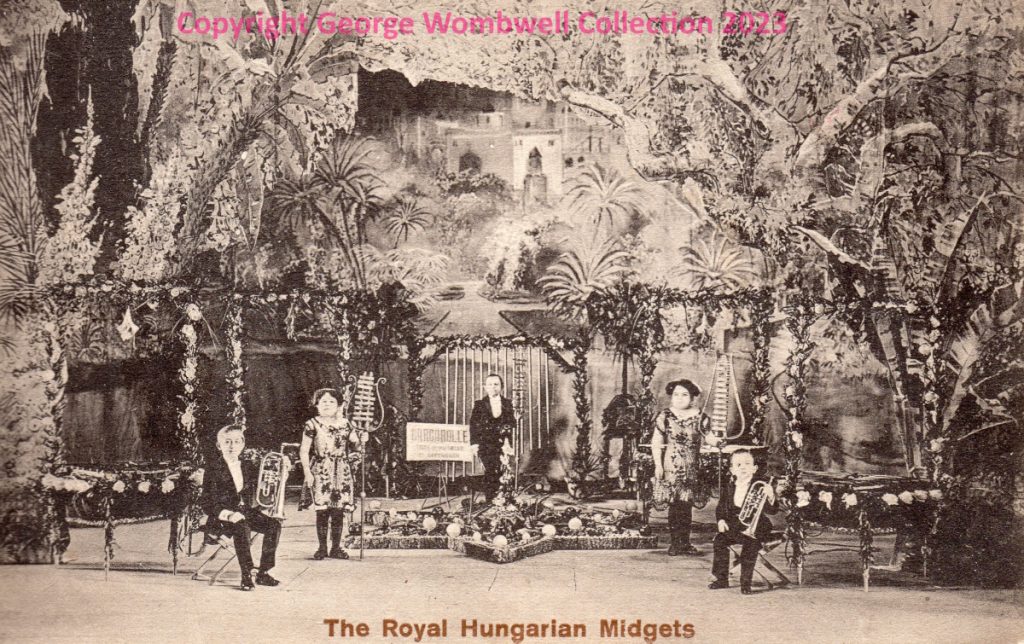

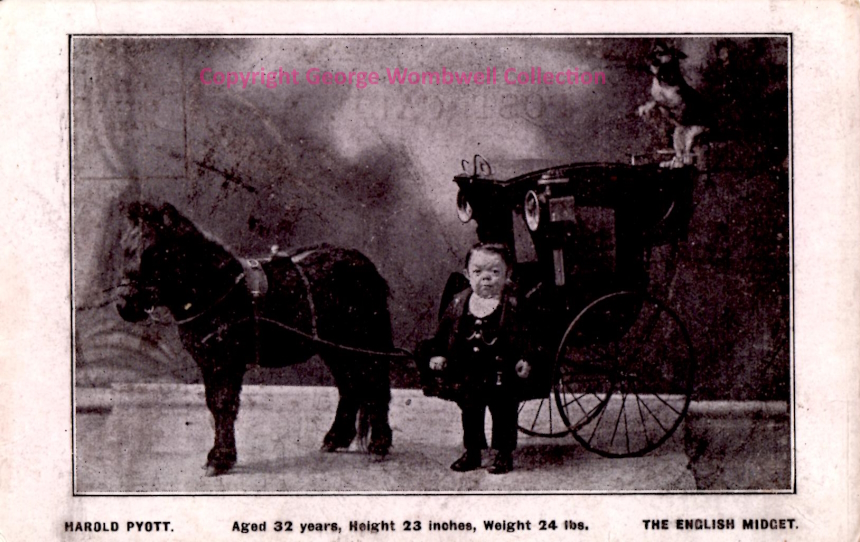

As a subject area, dwarfs were referred to as Midgets whenever they appeaed in newspapers advertising etc. The term “midgets” is considered outdated and offensive today. It’s more appropriate to use terms like “dwarf” or “little people.” That being said, historically, individuals with dwarfism were sometimes employed as court jesters or entertainers in various European royal courts. These individuals were often part of performances and events that amused the royal families and their guests. Later, particularly during the 19th and 20th centuries, participants were referred often as Midgets, as the above photographs show.

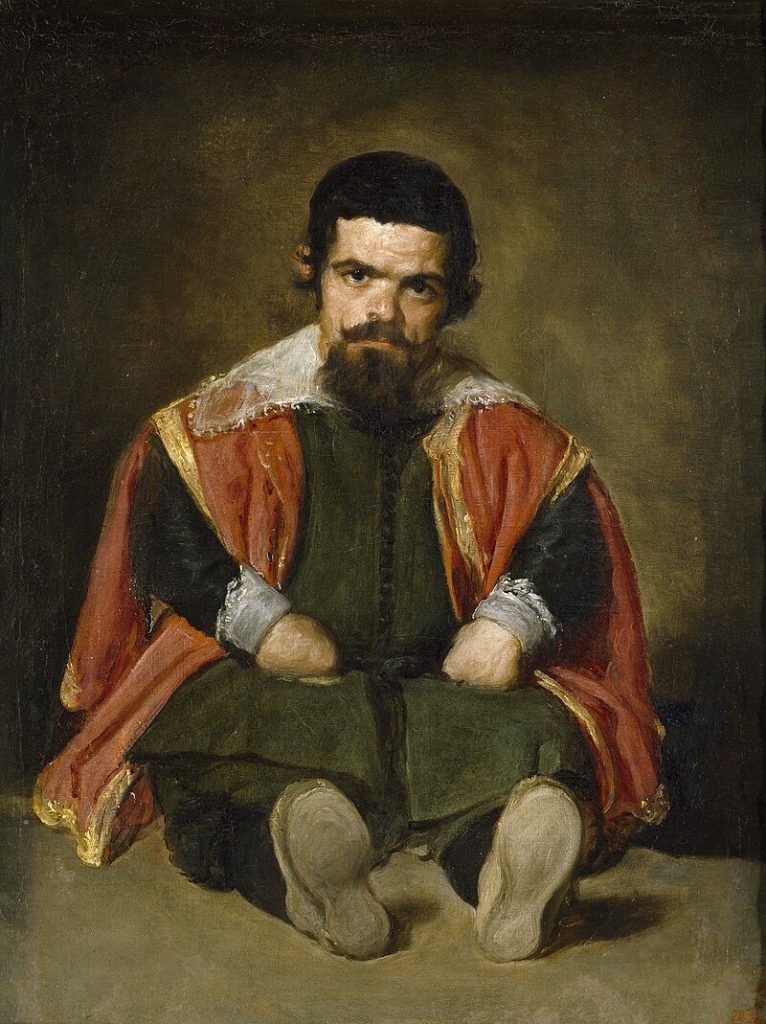

In art, the representation of individuals with dwarfism has been both historical and symbolic. Portraits and paintings from different periods may depict court jesters or dwarfs as a reflection of societal attitudes and norms at the time. These depictions could serve various purposes, such as entertainment, curiosity, or emphasizing social hierarchies.

The above card shows the Royal Hungarian Midgets circa 1910. A fairly obscure musical entertainment act headed by ‘Prince Andru’, alledgedly the world’s smallest man, traveling with a small group of dwarfs. Prince Andru apparently stood twenty-seven inches tall, weighed thirty-two pounds and was in his early twenties. The dwarfs perform in a beautiful well- lighted, airy miniature canopy erected on a stage, presenting a high-class program of vaudeville acts with musical numbers.

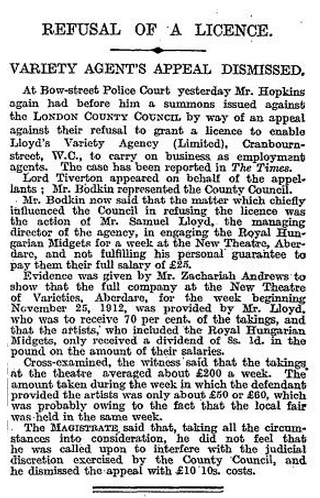

Whether this group of musicians were forced to do this to survive is not known, but it is possible in late Victorian England they would be seen as a speciality or novelty act. The Times newspaper in December 1913 recorded a dispute that was taken to law at Bow Streeet Court:

Although they had not been singled out for loss of earnings, it must have been disheartening to be considered not worthy of a full day’s pay!

There is a long history of the depiction of dwarfs in Court paintings, especially in Spain. Diego Velázquez, the prominent court painter to the King Philip IV during the 17th century.

Velázquez depicted a court dwarf in the service of King Philip IV of Spain. The title of the painting is commonly referred to as “Portrait of Sebastián de Morra,” although the actual identity of the sitter has been a subject of debate among art historians.

The painting is thought to have been created around 1645 during Velázquez’s second trip to Italy, where he was exposed to various artistic influences. Sebastián de Morra, the subject of the portrait, was a member of the court entourage and was likely employed for the amusement of the royal court. In the painting, Velázquez presents a sensitive and sympathetic portrayal of the dwarf.

One notable aspect of Velázquez’s treatment of the subject is the dignified and humanizing way in which he depicts Sebastián de Morra. Instead of relying on the typical conventions of the time that often sensationalized or exoticized dwarfs, Velázquez presents his subject with a sense of humanity, capturing his individuality and character.

The dwarf is portrayed in a relatively simple setting, emphasizing the direct gaze and engaging expression of Sebastián de Morra. Velázquez pays careful attention to details, such as the rendering of fabrics and textures in the clothing, showcasing his mastery of technique.

The portrait is characterized by its psychological depth and the artist’s ability to convey the humanity of the sitter. Velázquez was a master of capturing the personality and essence of his subjects, regardless of their social status or physical appearance.

“Portrait of Sebastián de Morra” is part of Velázquez’s larger body of work, which includes numerous portraits of the Spanish royal family and court members. It stands as a testament to Velázquez’s skill in portraiture and his ability to transcend the conventions of his time to create empathetic and humane representations of diverse individuals.

Harold Pyott, ‘The English Midget’ was another 19th century performer. According to the HeywoodHistory.com:

‘He was born in Stockport in September 1887 to Isaac and Harriet Pyott, who were both of average height, as were his two sisters. His parents died when he was 12 and he was placed under the care of his uncle, who took him to the local doctor for examination. Harold was found to be ‘normal’ in every way except size and weight. It was reported that he was visited by some of the most eminent doctors in Europe, who declared that he had a ‘strong and healthy constitution, but was certainly the smallest human being they had ever seen’.

Harold then lived at the Edinburgh home of his cousin William Beeley, who became his manager. William is listed in various records as working for the Post Office in both Edinburgh and Stockport. The exhibiting of short-statured people and midgets had been popularised by P.T. Barnum with the famous Tom Thumb (Charles Stratton). Barnum’s novelty act arrived in England in 1844 and Stratton became one the most highly paid and famous performers of the Victorian era. Many similar acts followed, including ‘Major Mite’, ‘Anita the Living Doll’ and of course Harold Pyott, who was billed as the ‘world’s smallest man’ and variously known as ‘Tiny Tim’, the ‘The English Midget’, the ‘English Tom Thumb’, or the ‘Living Doll’.

Harold travelled to various pantomimes and circus sideshows around Britain, Europe and South Africa for 35 years, and he performed before royalty on several occasions. Part of his act involved being carried around on the palm of a man’s hand and sitting in a top hat.’

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the use of wild animals in London theatres was a common and sensational practice. The use of animals, often exotic and dangerous, added an element of spectacle and excitement to theatrical performances. These displays were known as “animal acts” and were popular attractions in a variety of entertainment venues, including theatres, circuses, and menageries.

Wild animal acts in London theatres were diverse and ranged from dramatic reenactments of exotic scenes to more dangerous displays featuring trained animals. These performances could include scenes depicting jungle hunts, battles between humans and animals, or simply showcasing the exotic nature of the creatures. These acts were often included as part of larger theatrical productions or as stand-alone attractions between acts.

The animals used in these acts were sourced from around the world, and their presence in the city was a testament to the colonial and imperial interests of the time. However, the conditions in which these animals were kept and the treatment they received were often inhumane. Many animals suffered due to inadequate care, confinement, and the stress of performing in unnatural environments.

As public attitudes towards animal welfare began to shift during the late 19th century, concerns about the treatment of animals in entertainment grew. Activists advocated for better conditions and raised awareness about the ethical concerns associated with using wild animals in performances. Eventually, legal regulations and changing societal values led to the decline of such practices in theatres.

Overall, the use of wild animals in London theatres during the 18th and 19th centuries reflects a complex blend of curiosity, entertainment, and exploitation. It’s a historical reminder of how attitudes towards animals and entertainment have evolved over time.