Verso:

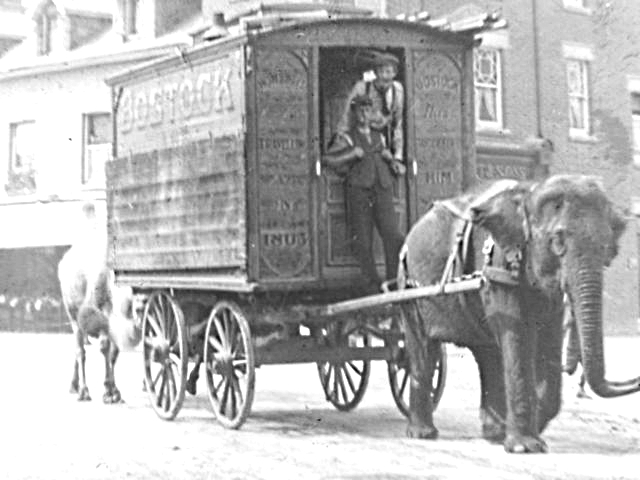

‘on Great North Road 1903’

‘McAlpine’

Pencil: ‘Noble Horse’

Verso:

‘on Great North Road 1903’

‘McAlpine’

Pencil: ‘Noble Horse’

On show at the Circus Hall of Fame Sarsota, Florid, USA.

Edward Cross, a notable wild beast merchant of the 19th century, owned and operated the menagerie at Exeter Exchange in London. Among his collection of exotic animals were several lions, and he famously named multiple lions “Wallace.”

Number of Wallace Lions:

It is documented that there were at least three lions named Wallace at different times. Each of these lions gained some degree of fame:

The practice of reusing the name “Wallace” for successive lions helped build a lasting brand and reputation for Cross’s menagerie, attracting visitors who were familiar with the famed lion by that name. This tradition of naming multiple animals with the same name is not uncommon in the history of menageries and zoos.

George Wombwell was a prominent British showman and the founder of Wombwell’s Traveling Menagerie, one of the most famous traveling animal shows in the 19th century. His menagerie was renowned for its exotic animals, and among them, a lion named Wallace became particularly famous.

Fame and Legacy:

George Wombwell’s lion, Wallace, remains one of the most famous lions in the history of traveling menageries. Wallace’s reputation for being a magnificent and gentle lion made him a star attraction and helped cement George Wombwell’s legacy as a leading showman of his time. The story of Wallace highlights the public’s enduring fascination with exotic animals and the rich history of animal exhibitions in the 19th century.

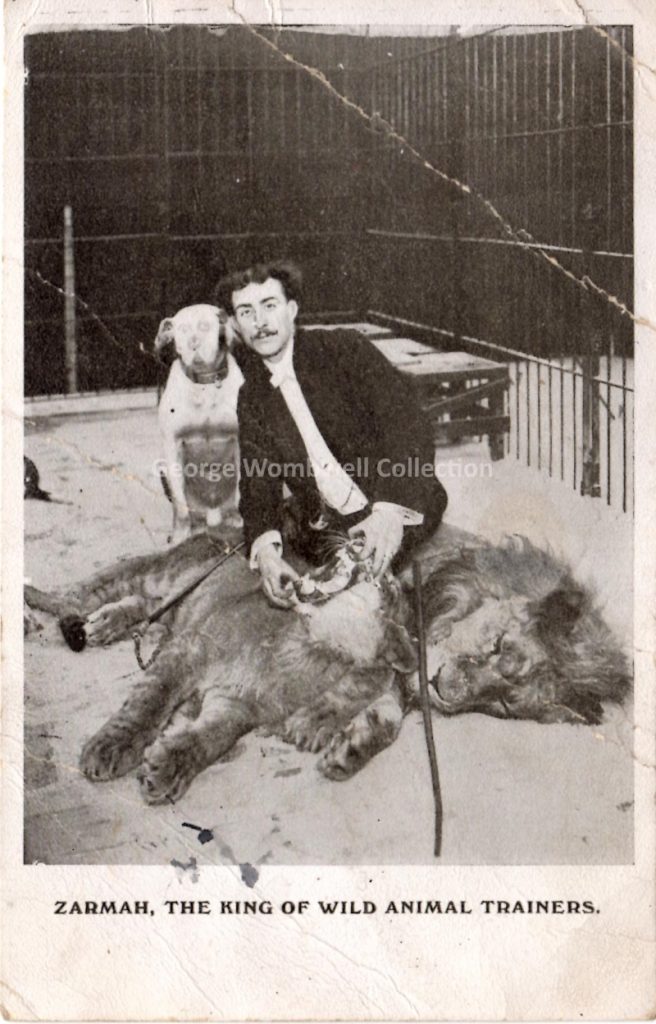

However, the Wallace depicted above was from the USA, and, according to the card, was from the Wombwell and Bostock Wold Animal Show. Reported to have killed 3 of its trainers and had to be ‘executed’.

It was Frank Bostock that went to the USA in the late 1800s and successfully traveled the country with his Wild Animal Show. He also had a permanent site on Coney Island, New York.

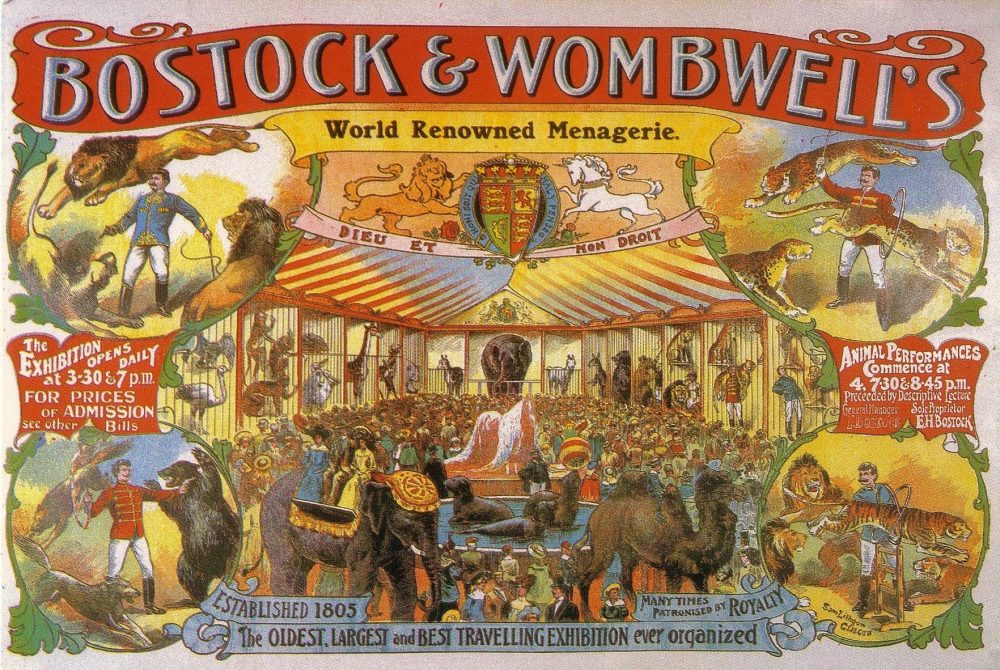

Frank C. Bostock, known as the “Animal King,” was a pioneering figure in the world of traveling menageries and animal shows. Originating from a family deeply entrenched in the circus and menagerie business in the UK, Bostock expanded his operations internationally, achieving remarkable success in New York in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Born in 1866 in England, Frank Bostock was part of the famous Bostock and Wombwell menagerie family. From a young age, he was immersed in the world of exotic animals and show business. Frank eventually branched out to create his own menagerie, distinct from his family’s legacy, which would go on to become a global sensation.

In the early 1890s, Frank Bostock brought his menagerie to the United States, where he quickly made a name for himself. New York, with its burgeoning entertainment industry and appetite for spectacle, provided the perfect setting for Bostock’s grand exhibitions.

Frank Bostock’s tenure in New York marked a significant chapter in the history of traveling menageries and animal exhibitions. Through his innovative approach to animal training and showmanship, Bostock captivated audiences and set new standards for the industry. His legacy as the “Animal King” endures, reflecting his contributions to entertainment, animal welfare, and cultural history.

I. Introduction

Travelling menageries were a prominent feature of British society during the 19th century, offering audiences the opportunity to encounter exotic animals from around the world. This literature review(without references) explores the multifaceted impacts of travelling menageries on British society, focusing on their social, cultural, and economic dimensions.

II. Historical Background of Travelling Menageries

Travelling menageries emerged in Britain during the late 18th century, capitalizing on public fascination with exotic wildlife and the growing interest in natural history. These exhibitions featured a diverse array of animals, ranging from elephants and lions to monkeys and birds, and were often accompanied by spectacle and entertainment. Menageries toured cities and towns across the country, drawing crowds eager to witness the wonders of the natural world.

III. Social Impacts of Travelling Menageries

Menagerie exhibitions provided a form of entertainment accessible to people of all social classes, offering a rare opportunity for individuals to interact with exotic animals. Working-class audiences, in particular, were drawn to menageries as a means of escape from the drudgery of daily life. However, debates surrounding animal welfare and ethical treatment also emerged, sparking discussions about humanity’s relationship with the natural world.

IV. Cultural Impacts of Travelling Menageries

Travelling menageries played a significant role in shaping British culture during the 19th century, influencing artistic expressions, literary works, and popular imagination. Artists and writers drew inspiration from menagerie exhibitions, incorporating exotic animals and scenes into their creations. Moreover, menageries contributed to the construction of narratives of exoticism and colonialism, reflecting broader cultural attitudes towards the “other” and the fascination with the unknown.

V. Economic Impacts of Travelling Menageries

As commercial enterprises, travelling menageries had a substantial economic impact on British society. Menagerie owners operated lucrative businesses, charging admission fees and selling souvenirs to patrons. The tours of menageries also provided economic opportunities for local communities, stimulating commerce and attracting visitors to towns and cities. However, the profitability of menageries was often precarious, with financial challenges leading to the eventual decline of the industry in the late 19th century.

VI. Methodological Approaches in Studying Travelling Menageries

Scholarly research on travelling menageries employs a variety of methodological approaches, including archival research, historical analysis, and cultural studies. Primary sources such as newspaper articles, diaries, and advertisements provide valuable insights into the experiences of audiences and the operations of menageries. However, researchers must navigate challenges such as biased representations and gaps in the historical record when studying this topic.

VII. Themes and Trends in the Literature

Existing scholarship on travelling menageries reveals several recurring themes and trends. Scholars have explored the intersections of entertainment, education, and exploitation in menagerie exhibitions, as well as the broader implications for understanding human-animal relationships. However, gaps in the literature persist, particularly regarding the perspectives of marginalized groups and the long-term legacies of menageries on British society.

VIII. Conclusion

Travelling menageries left a lasting imprint on 19th-century British society, influencing social interactions, cultural representations, and economic dynamics. Despite their eventual decline, menageries continue to fascinate scholars and enthusiasts alike, offering a window into a bygone era of exploration and spectacle. By examining the social, cultural, and economic impacts of travelling menageries, we gain valuable insights into the complexities of human-animal relations and the intersections of entertainment, commerce, and culture in the Victorian era.

In the colorful tapestry of entertainment history, Frank Bostock’s menagerie stands out as a fascinating chapter that brought the exotic wonders of the animal kingdom to the doorsteps of audiences. Born in 1866, Frank Bostock was a showman and menagerist who created a traveling spectacle that captivated the imaginations of people across continents.

Bostock’s journey into the world of menageries began at a young age. His fascination with animals and a keen sense of showmanship led him to establish his own menagerie, showcasing a diverse collection of creatures from every corner of the globe. Bostock’s vision was not just about displaying exotic animals but creating an immersive experience that transported spectators to far-off lands.

What set Bostock apart was his mobile menagerie – a traveling caravan of wonders that brought the allure of the wild to both urban centers and rural areas. From lions and tigers to elephants and exotic birds, the menagerie featured a breathtaking array of creatures. This traveling spectacle became a cultural phenomenon, providing a taste of the exotic to audiences who might never have the chance to see such animals otherwise.

Bostock’s menagerie wasn’t merely about entertainment; it also served an educational purpose. His shows often included informative talks about the habits, habitats, and characteristics of the animals on display. Bostock sought to cultivate a sense of wonder and respect for the natural world, fostering a connection between people and the creatures that shared the planet.

Bostock’s menagerie gained royal approval when he presented his traveling show to King Edward VII, further solidifying its prestige. Beyond the shores of England, Bostock expanded his menagerie empire internationally. The success of his shows in the United States and Australia attested to the universal appeal of his carefully curated exhibits.

Running a traveling menagerie posed numerous challenges. Animal welfare concerns were raised, and Bostock faced criticism for the conditions in which the animals were kept. However, it’s important to contextualize these issues within the historical understanding of animal care during the time. Bostock, in his era, was at the forefront of popularizing and showcasing wildlife.

Frank Bostock’s menagerie left an indelible mark on the history of entertainment. His innovative approach to combining education with spectacle laid the groundwork for future zoos and wildlife exhibitions. The legacy of Bostock’s menagerie endures in the collective memory of those who experienced the thrill of encountering exotic animals in the midst of their everyday lives.

In the grand tapestry of showmanship, Frank Bostock’s menagerie remains a vivid thread that weaves together the realms of entertainment, education, and wildlife appreciation. Bostock’s traveling spectacle brought the wild to the urban and rural landscapes, leaving an imprint on the cultural fabric of the times. While the methods and ethical standards of animal exhibitions have evolved, Bostock’s menagerie remains a fascinating chapter in the history of human fascination with the wonders of the animal kingdom.

During the Victorian era (1837-1901), exhibitions were a popular form of entertainment and education for the public. These exhibitions showcased various aspects of science, industry, art, and culture, attracting large crowds eager to witness new and exotic discoveries from around the world. One fascinating and recurring attraction at these exhibitions were menageries.

Menageries were collections of live, exotic animals from different parts of the globe, displayed for the public’s amusement and curiosity. They were essentially traveling zoos that brought together a wide variety of creatures that most people in the Victorian era would never have had the chance to see otherwise. Menageries at Victorian exhibitions often included exotic mammals, birds, reptiles, and sometimes even marine life.

Here are some key aspects of menageries that attended Victorian exhibitions:

One of the most famous examples of a Victorian-era exhibition featuring a menagerie was “The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations” held in London in 1851. This event showcased a wide range of exhibits, including a menagerie featuring live animals from different parts of the world. The inclusion of menageries in such exhibitions was a testament to the allure of exotic wildlife and the thirst for knowledge and adventure that defined the Victorian era.

The travelling menagerie, which refers to the practice of showcasing exotic animals in traveling shows and circuses, can be understood in the context of imperialism and its association with Great Britain during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The menageries were closely tied to the imperial ambitions of Britain and other European powers during this period. Here are some key points to consider:

In conclusion, the travelling menagerie can be seen as a manifestation of British imperialism during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a practice closely tied to the exploration, exploitation, and display of the empire’s conquests, showcasing the exotic and wild aspects of lands under British control. Today, the historical context of the travelling menagerie serves as a reminder of the complexities and consequences of imperialist endeavors and the changing attitudes toward animal welfare and conservation.

Image copyright GeorgeWombwell.com 2023, All rights reserved.

There is an emergence of interest in the burial sites of large beasts that died across the country. Most are reported in local newspapers of the time and invariably the beasts passed away as part of a travelling menagerie. Recently, one such animal, an elephant, was reported to have deceased and been buried in a local graveyard in Kingswood, Bristol (1891).

There may be various reasons for burying elephants where they die, but one reason may have its roots in Indian tradition.

The practice of burying an elephant where it dies is rooted in the cultural and religious traditions of India. Elephants hold a special place in Indian culture, where they are revered as sacred and often associated with various Hindu deities such as Ganesha, the elephant-headed god of wisdom and prosperity.

When an elephant dies, especially in regions where they are considered significant, there is a belief that it should be accorded a respectful farewell and burial. The burial rituals vary depending on the local customs and traditions, but the underlying sentiment remains the same—to honor the majestic creature and ensure its passage to the afterlife.

In some instances, the burial of an elephant may involve a communal effort, with local communities and authorities coming together to perform the rituals. The burial site is often chosen carefully, taking into consideration factors such as proximity to water sources and the elephant’s natural habitat. The process typically involves digging a large pit or trench, deep enough to accommodate the massive body of the elephant.

The burial itself can be a complex and time-consuming process, given the size and weight of an elephant. The local community may use ropes, pulleys, and machinery to carefully lower the elephant’s body into the burial pit. The grave is then covered with soil, forming a mound or raised platform to mark the resting place of the elephant.

The practice of burying elephants holds significance beyond the physical act of burial. It is believed to demonstrate reverence for the animal and symbolize a respectful farewell, ensuring that the elephant’s spirit finds peace in the afterlife. Additionally, burying the elephant near its natural habitat is seen as a way to maintain the ecological balance and pay homage to the creature’s role in the ecosystem.

It is worth noting that the burial of elephants is not a widespread practice throughout India. It is more commonly observed in regions with a long-standing history of human-elephant coexistence, where elephants are revered and considered an integral part of the local culture and mythology.

While burying an elephant is a culturally significant practice, it is also important to consider the environmental impact and practical considerations associated with such burials. Authorities and local communities need to strike a balance between preserving cultural traditions and adhering to environmental regulations to ensure the conservation of the ecosystem.

In recent years, there has been an increased emphasis on wildlife conservation and the implementation of more sustainable practices. As a result, alternative methods such as natural decomposition or cremation may be considered as viable options to address the ecological concerns associated with large-scale burials.

Overall, the practice of burying elephants where they die reflects the deep cultural and spiritual connection between the Indian people and these majestic creatures. It serves as a testament to the rich tapestry of traditions and beliefs that shape India’s diverse cultural landscape.

Here is answer to our question: Do you know George Wombwell?

“Yes, I am familiar with George Wombwell. He was an English menagerie owner and showman who lived from 1777 to 1850. He is particularly famous for his traveling menagerie, which he took around the country exhibiting exotic animals such as elephants, lions, tigers, and bears. His menagerie became one of the most famous in the world and he is considered one of the pioneers of modern zoos. He was also known for his philanthropy, and was a supporter of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.”

Nothing about dog fights in that answer. So what was response when the question was : Did George arrange lion fights?

“There is no evidence to suggest that George Wombwell arranged dog fights. In fact, Wombwell was known for his love of animals and was opposed to any kind of cruelty towards them. He was a proponent of treating animals with kindness and respect, and he took great care to ensure that the animals in his menagerie were well looked after. Wombwell’s legacy is that of a pioneering showman who helped to popularize the idea of exhibiting exotic animals to the public, and of a philanthropist who cared deeply about the welfare of animals.”

Maybe we cannot trust a chatbot, but clearly the underlying data suggest otherwise! It’s nice to know that consensus agrees with this websites persuasive , but well researched arguments.

An rare monochrome photograph and a monochrome postcard have been added to the archive.

Date unknown, but the menagerie is utilising electric lights. Verso states the menageire was sold at Newcastle.

The photographic angle of the second image is interesting: Who’s looking at who!

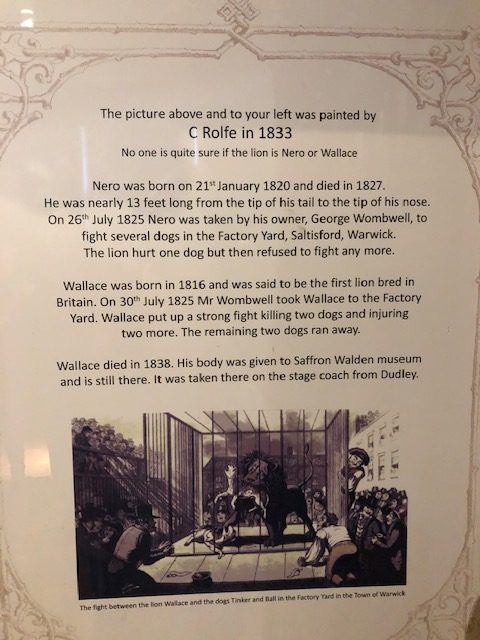

About 18 months ago, I was contacted by one Prunella, a lady from Canada, advising me she had seen a painting of Wallace the Lion at a museum in Warwick, England.

This was her explanation at the time:

‘My mother’s maiden name was Ethel GRACE Wombwell – my 3X great grandfather John (1774 – 1845) was a son of John Wombwell and Sarah Rogers.

In reference to the lion fights…. There is a very small museum in Warwick that has a painting of a lion (either Nero or Wallace) and a poster about the fight… If this is your correct email, I will attempt to send the pictures of these that I took last year. My brother lives near Warwick and I have asked him to send me the name of the museum.’

Prunella recently replied to an email from me with the following information:

‘The place in Warwick is St John’s House Museum, CV34 4NF’.

Since it has been two years since I was first alerted to its existence, I checked out the current details, for anyone wishing to visit the museum.

The Museum is currently closed for a re-location within Warwick, but are still open to deal with shop sales and family history research enquiries.

Exciting developments are afoot to re-locate the museum in 2022 to Pageant House, Jury Street, Warwick.

However, on further research I was informed that the painting is no longer at the museum, irrespective of which building, but in their Hawkes Point storage facility.

Luckily, further detective work revealed that the painting, attributed to Rolf, is documented on splendid ArtUK website.

https://d3d00swyhr67nd.cloudfront.net/w944h944/collection/WAR/WARMS/WAR_WARMS_39-001.jpg

Unfortunately, due to copyright it is not possible to show it here. However, our intrepid Canadian contact, did the honours and produced these two fine photographs.

It is though, an accomplished portrait of a fictional lion, face on. Looks quite sweet! Not the ideal representation a a ‘killer’ lion. Maybe that is poetic justice given the 200 year old lie that Wallace…well, read my Volume One for the real story of the lion fight!